The long-term outlook for Permian Basin producers may not be so bright, based on a new study showing production from older tight oil wells sinking faster than expected.

The study by Wood Mackenzie, Everything is Accelerating in the Permian, Including Decline Rates says the “terminal decline rate” is far greater than the widely used rule of thumb of 5-10% a year.

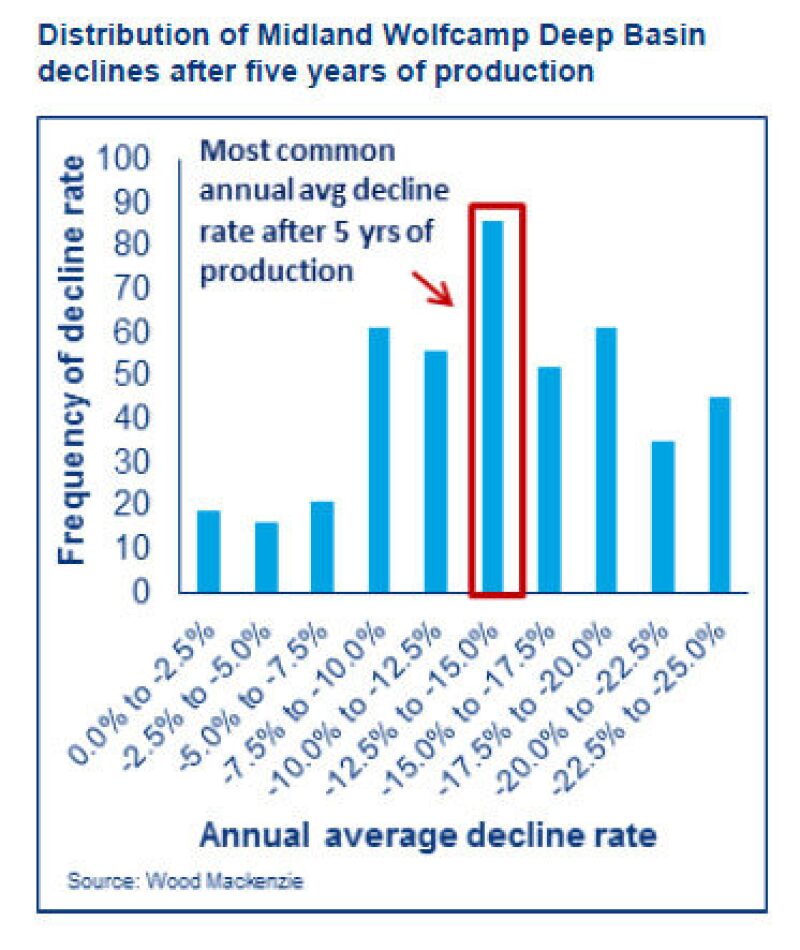

“For Wolfcamp wells in terminal decline… the most common occurrence is a decline rate of 14% a year,” said Robert Clarke. research director for Lower 48 Upstream at Wood Mackenzie.

Unconventional wells are known for rapid decline rates. Permian wells often produce 40% of the oil and gas they are expected to produce over their lifetime in 36 months, according to the report. But the conventional wisdom has been that sometime after year 5, the decline rate flattens out for a slow, steady decline lasting for decades.

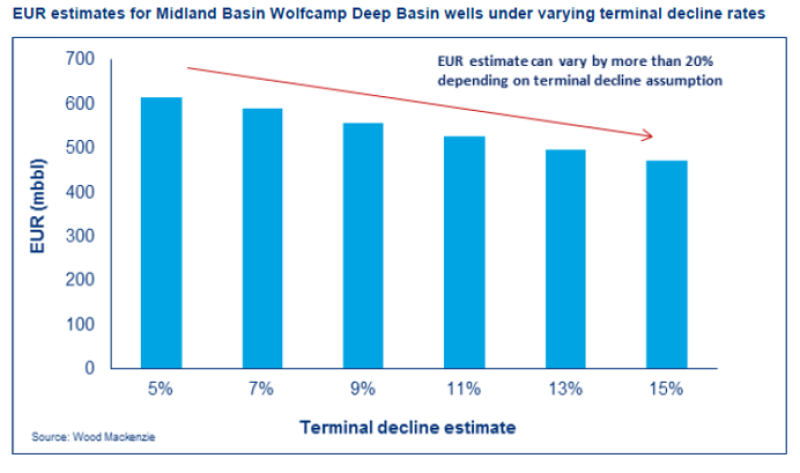

Decline rates of 14% could be a problem because the report authors say estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) calculations are generally based on the 5-10% rule of thumb, with many companies assuming a 5% rate.

“The push for 5% is very aggressive,” said Ryan Duman, a principal analyst for Wood Mackenzie who co-authored the report, adding that “from an EUR perspective that can have a dramatic impact on what you are showcasing.”

This chart (Fig. 1) is an example of that. There is a nearly a 100,000 bbl difference in the EUR of the 5% and the 15% decline rate wells. The difference in the later years is even sharper if one considers that about half the production occurs during the first 5 years.

Wood Mackenzie launched the study after learning about older wells in the Permian where production was declining faster than expected. The study looked at annual decline rates for wells at least 6 years old in Permian’s prolific Wolfcamp play using the firm’s North American Well Analysis tool.

“This was our first deep, deep dive into the topic. We did it because we wanted to understand the impact of the aggressive completions we're seeing in the Permian,” said Clarke. As part of the study, it compared the decline rates in tight oil wells in the Permian with wells in the Bakken and with conventional wells in the Permian. Those wells had decline rates that generally fit within the widely used 5-10% per year range.

The decline rate in the wells analyzed were clustered in a 12.5% to 14% range (Fig. 2). While a significant number of wells declined less than 10% a year, a comparable number of wells declined at rates as high as 25% a year.

Duman said feedback from those in the field has been positive, but engineers have questioned whether the sample includes wells that are not yet in terminal decline, which could inflate the rate.

The decline curve for tight oil wells can be broken into three parts: early peak production where the declines are steepest, a transition period where production and declines slow, and terminal decline where the decline rate goes down a bit and the curve flattens.

“We are not putting a stake in the ground and saying everyone should be modeling a 14% decline rate,” Duman said. But the consultancy advises that “there are risks in using a shallow (low) decline rate.”

Wells Missed

Talk of faster than expected production declines in the Permian sounds odd at a time when production there has risen so fast pipelines are at capacity.

The old wells in the study are easy to miss. Less than 20% of the wells in the area studied were in the 6 years old or older category. Even in their prime, these wells would not likely have equalled the output of wells now with laterals twice as long, which are fractured far more intensively.

There were few industry reports on late life decline rates to draw on from earnings reports or investor presentations.

“Companies are extremely quick to highlight initial production rates and cumulative production rates,” Duman said, adding that no one says, “Remember that 5 years ago there was a monster well? Here is how it is doing today.”

A faster decline rate for older Permian wells is not going to have a noticeable impact on Permian production totals anytime soon. A 14% terminal decline rate only reduces the basin-wide total by 125,000 b/d by 2025. By 2040 it could hit 800,000 b/d.

Individual companies and investors have a stronger motivation to pay attention to faster decline rates. For companies with budgets limited by the cash generated from operations, which is becoming the norm, faster decline rates are bad for two reasons—it means there is less money to spend on things such as well workovers, and more wells must be drilled and completed to maintain or add production.

“If shale plays are classified as drilling treadmills, the Permian treadmill could actually be set on an incline,” Duman said.

“To date, the bulk of Permian M&A (mergers and acquisition) activity has targeted undeveloped tight oil acreage, but we are starting to see more developed properties” sold, Duman said. The ultimate value of deals for older wells will vary widely based on the decline rate.

Better Care

The report covers activity in a fast-changing landscape where there are operators looking for ways to get a lot more oil out of this tight rock.

“Permian producers have been incredibly resourceful in the face of every challenge they've encountered so far. It's certainly likely that the accelerated decline rate we saw will improve a little bit,” Clarke said.

Tight oil development has changed considerably since the days the wells they studied were built.

Many of the wells they studied reached their terminal decline years during the deepest part of the recent downturn when many companies cut spending on well work that could have slowed declines. With oil prices up, the payoff for working on them is greater.

There are new tools that can help, such as automated pump controls that use artificial intelligence to maximize the oil produced from each pump stroke. But horizontal wells are now generally two miles long—twice the length in the older wells studied—which could make them costlier to maintain. The low volumes of oil produced late in a well’s life may not justify doing those jobs, Duman said.

Future wells will likely be drilled in lower-quality rock in the Permian by operators that have long focused on developing the best spots first. Those wells will be more likely to be near older wells, adding the risk of interaction that can damage older wells and reduce the potential output of new ones.

“The reality is increasingly tighter spacing and well interference is becoming more prevalent. That is another mechanism that accelerates decline,” Duman said.

But reports from the recent Unconventional Resources Technology Conference showed that there is a greater awareness of the need to get more out of older wells.

Occidental Chief Executive Officer Vicki Hollub said the company is planning a multiwell field test to see if carbon dioxide injection can increase production from older tight oil wells.

And the objectives announced for the next West Texas Fracturing Test Site—an industry-government consortium backing unconventional well R&D—will include understanding the impact of current completion methods and what can be done to get significantly more from each well.

“This research will establish the foundation for investigating enhanced oil recovery techniques which we plan to investigate,” said Jordan Ciezobka, manager for research and development for the Gas Research Institute, which managed the first test site in the Midland Basin.

Given all the variables it is impossible to predict what the decline rate will be as wells drilled now grow old. Clarke said that “given all the reasons we present in the paper; it may still stay higher than the proxy value from other tight oil plays. Maybe the most common decline rate moves from 15% to 10%. We will have to wait and see.”

To learn more, a podcast where the authors of the report discuss decline rates can be found here.