|

|

|

Questions posed by 2015 SPE President Helge Hove Haldorsen | Answers provided by Theodore W. Pirog, Energy Advisor, Corporate Strategic Planning, Exxon Mobil Corporation | Robert Gardner, Manager, Economics and Energy Division, Corporate Strategic Planning, Exxon Mobil Corporation |

ExxonMobil’s Long-term Global View of Energy Demand and Supply

Every year, a core team in ExxonMobil produces the acclaimed The Outlook for Energy: A View to 2040. Based on historical data, current developments, trends, and assumptions about the future (e.g., how energy efficiencies will improve, the number of cars on the road going forward), the ExxonMobil team projects demand and supply for all energy sources, including fossil fuels and renewables, and the resulting global energy mix. For petroleum engineers, the outlook for global oil and gas demand is of particular interest. Are we in a sunset industry or not?

I sat down with ExxonMobil’s Rob Gardner and Ted Pirog to discuss a number of key issues that SPE members are keenly interested in. Their very interesting perspectives are presented below.

You have predicted the global energy future for quite some time. In hindsight, how do old predictions compare with actuals? For example, are the predictions made in 2000 for 2014 spot on?

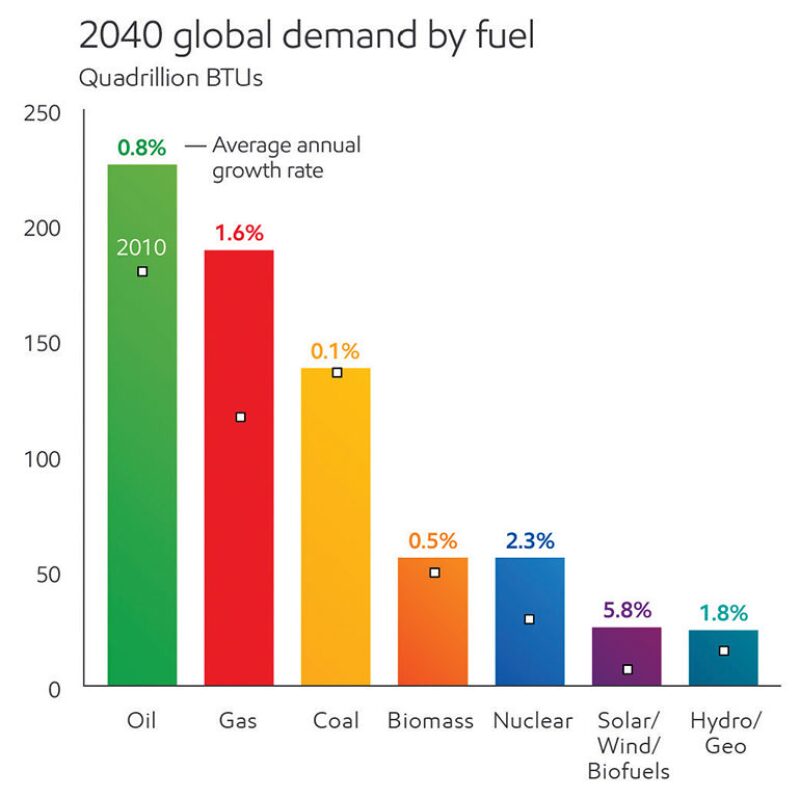

ExxonMobil has been developing The Outlook for more than six decades, so we have a lot of experience on how our predictions compare. Over the past 15 years, we have seen numerous events that have dramatically changed energy supply and demand. For example, the surge in China’s economy, a global economic recession, the development of unconventional oil and gas, and the devastating tsunami in Japan with its ripple effect on nuclear power policies. To illustrate how The Outlook has held up over the past 15 years, our forecasts since 2000 for global energy in 2010 ran fairly consistently around 500 quadrillion Btu, averaging about 510 quads, or about 3% below 2010 actual results. Note that historical results are lagging and often restated, so we only have the benefit of the final data for 2010 as reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Which are the hardest to predict?

It is always challenging to predict the random events such as social unrest, political upheaval, and catastrophic events such as tsunamis. Although these events can be devastating and can affect global energy trends, the long-term trend of energy demand growth driven by population and gross domestic product (GDP) has remained very consistent. In developingThe Outlook, we tap into a wide range of sources, from our own research scientists and university researchers to help us evaluate emerging technologies, to people in other industries, such as automobile companies and electric power providers. We also engage with policy makers worldwide, who are keen to exchange views with us on what makes sense for future consumers and societies.

What has impressed you the most when it comes to the energy industry being able to step up to supply the growing global energy demand?

The Outlook for Energy represents a “good news story” about the prospects for future energy. We live in a world with vast resources not only geologically, but more importantly, in terms of human innovation. New technologies in the world of energy continue to improve, helping to produce the energy needed to improve living standards everywhere. History continually shows that the energy industry is very creative and adaptive to solving global energy challenges.

Is the marketplace (as in historian Adam Smith’s theory of the invisible hand) picking the winners in technology and preferred energy sources or are governments picking the winners through incentives, mandates, laws, and regulations?

We see both. Clearly, the oil and gas industry has made tremendous progress over the last decade on developing unconventional oil and gas supply. We have also seen CO2 reductions in North America as a result of the market choosing low-cost natural gas over coal for power generation. But at the same time, the government, through tax incentives, is pushing wind and solar, which cannot compete with other energy sources on a level playing field. Over the long term, government subsidies for energy production and policies that pick winners and losers in the competitive energy space are counterproductive to broadly meeting society’s needs. There is a role for government to support precommercial energy research and development, which may provide broad-based economic benefits across many sectors of the nation.

What megatrends do you see affecting energy demand over the next 25 years? What do you think will surprise us the most in 2040 when it finally arrives?

We consider many megatrends like smart cities and growing regulations due to climate change. One megatrend that we highlight in our current Outlook is the dramatic expansion of the world’s middle class. The Brookings Institution recently estimated that the number of people who earn enough to be considered “middle class” will reach 4.7 billion people by 2040, up from 1.9 billion in 2010. When people earn enough to have discretionary income beyond their daily needs, they are considered as middle class. As people cross this threshold, it allows people to obtain durable consumer goods, such as electric appliances and cars, and services, such as higher education and advanced medical care. People are able to improve their quality of living through temperature-controlled rooms and less densely populated homes. All these improvements depend on energy and impact global energy demand. The growth of the middle class is accompanied by other societal changes that drive energy use, such as improved infrastructure, electrification, and urbanization.

Looking at similar forecasts from Shell, BP, McKinsey, US Energy Information Administration (EIA) and others, they all pretty much agree. What would have to happen for the outlook to 2040 to be really wrong one way or the other?

There would need to be a dramatic change in the economic and/or demographics to affect long-term energy demand. Also consider that the scale of the energy industry is so large that it takes decades for commercial development and adoption of new technologies. For example, if a revolutionary breakthrough in technology occurred this year, we would likely not see an impact at the global scale for decades. Just remember that modern oil production started in the 1860s and it took more than a century before it was a major contributor globally. As you point out, there are other outlooks and they share similar trends, but as you look in the details, you can find some important distinctions like in natural gas, coal, and nuclear utilization driven by different technology, efficiency, and government policy assumptions.

As the 2015 president of SPE, college students ask me if I can guarantee that petroleum engineers will be needed in 25 years from now. What should I say?

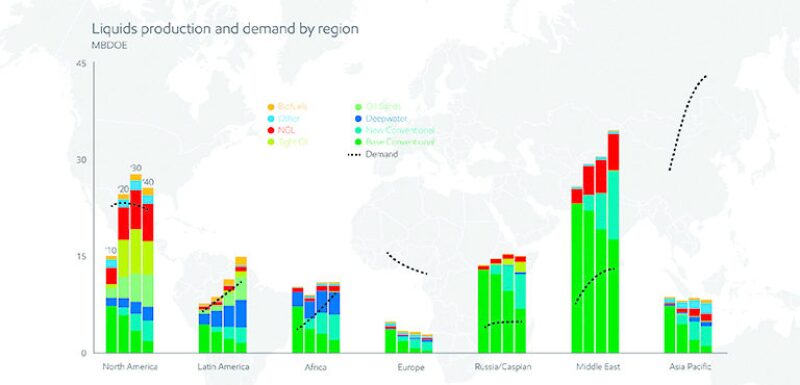

The scale of the upstream industry is enormous. The world currently uses about 90 million BOPD of oil and 350 Bcf/D of gas. By 2040, we project that oil demand will grow by 30% and gas demand by over 60%. The IEA estimates that upstream oil and gas activities will require USD 650 billion/yr to maintain existing and future production. You can clearly see the scale of the activity required and the need for the brightest engineers and scientists to meet the growing global demand for energy.

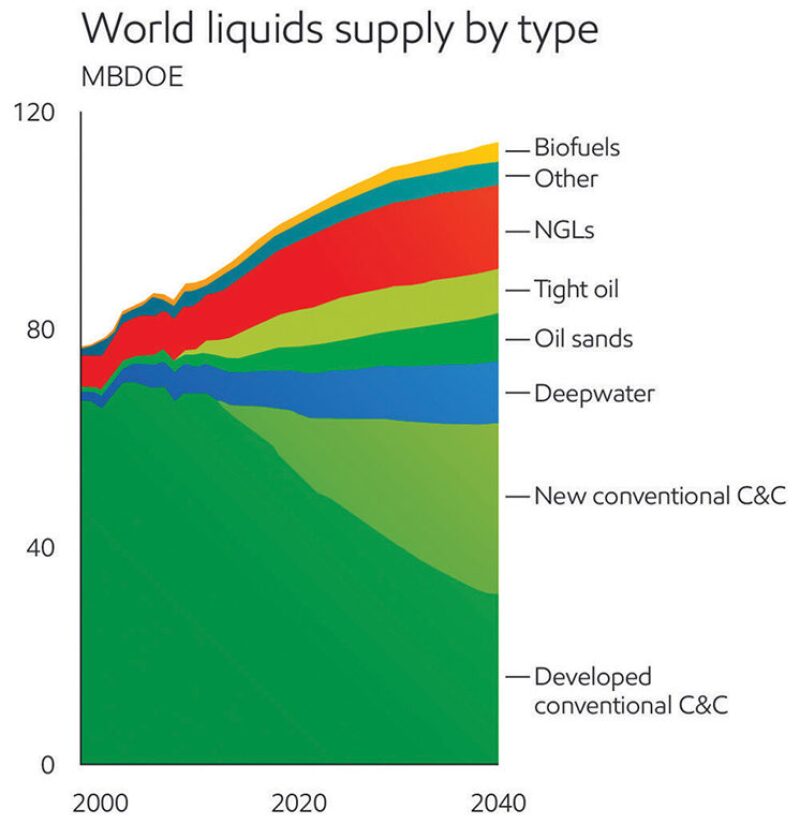

Conventional production will decline at the same time that global demand is rising. What is the gap that needs to be filled in the next 25 years? How many billion barrels of new oil production do we need to find and put on stream during the next 25 years?

We expect that in order just to offset declines in existing conventional oil developments, the world will need to increase production by more than 15 million BOPD by 2025 and more than 30 million BOPD by 2040. At the same time, demand will grow by 15 million BOPD by 2025 and 25 million BOPD by 2040. Therefore, the gap between current development and future demand is 30 million BOPD by 2025 and 55 million BOPD by 2040. The world will require almost 350 billion barrels of new oil production over the next 25 years.

In your mind, is there a “survival of the fittest” fight between fossil and renewable energy sources or is it more of an “all of the above please” to cover the huge and rising global energy demand?

Given that global energy demand will increase by 35% from 2010 to 2040, it makes sense to consider all forms of energy. There are numerous factors that impact consumer choices like economics, government policies and environmental impacts. One factor that limits the growth of renewables is their intermittent supply. As penetration of intermittent renewables increases, extra steps must be taken to ensure a reliable flow of electricity to consumers. These steps create additional, often overlooked, costs. For example, additional generating capacity, such as natural gas-fired plants, must be made available to back up wind and solar during times when the sun is not shining and the wind is not blowing.

Do you think that some “not invented yet” energy sources can change the picture completely? Will we be able to cancel gravity one day and come to work in flying cars?

We monitor a wide variety of technology areas to identify any potential game changers and develop scenarios to determine their impact on energy demand. Although these events can significantly change the energy picture, it takes decades to see their impact. As mentioned previously, history shows that these breakthroughs take time to commercialize due to the size, scale, and complexity of the modern energy industry. For example, nuclear power was developed in the 1950’s and currently meets 5% of global energy demand.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has suggested that to avoid a rise of 2°C in temperature, natural gas needs to replace coal. A recent study at University College London suggests that significant portions of today’s reserves of coal, oil, and gas need to remain in the ground and unused through 2050 if we are to have a 50% probability of remaining below a 2°C increase in temperature. What are your comments?

ExxonMobil makes long-term investment decisions based on our rigorous, comprehensive annual analysis of the global Outlook for Energy, an analysis that has repeatedly proven to be consistent with the IEA World Energy Outlook, the EIA Annual Energy Outlook, and other reputable, independent sources. We see population, global economic activity and energy needs increasing for the world over The Outlook period, and that all economically viable energy sources will be required to meet these growing needs. Our Outlook for Energy does not reflect a “business as usual” climate policy scenario and for many years has explicitly accounted for the prospect of increasingly stringent greenhouse gas policies. While we believe governments will take action to address the risk of climate change, we believe a policy scenario that completely transforms the global energy system at the unprecedented rate, pace and cost needed to stabilize greenhouse gas levels as contemplated in the 2°C scenario is highly unlikely. Except for the recent switch from coal to natural gas in the US, deployment rates of low carbon technologies have been dramatically below the pace needed to meet a 2°C pathway. More can be read at ExxonMobil’s website: http://corporate.exxonmobil.com/en/current-issues/climate-policy/climate-policy-debate/overview.

Assuming that renewables account for a significant share of energy in 2100, do you see the suppliers as current energy companies that have transformed themselves? Or will the classic E&P companies have folded 85 years from now and become a whole new breed of companies with a different core competence?

The year 2100 is far in the future and well beyond our Outlook, so estimating the global energy mix is extremely challenging. Currently, the IEA estimates that there is more than 200 years of natural gas supply, 150 years of oil supply, and enough coal to last many centuries. Technology has always found ways to expand our resource base. For example, the remaining crude and condensate resource base has more than doubled since 2000. So I would expect oil and gas to meet future energy needs for a very long time. We use The Outlook to guide our investment decisions and strategies so we can adapt to any changing market conditions.

Investors are saying to oil companies: Do not go into renewables. We diversity, you don’t. Stay with what you know. In this scenario, how can “Big Oil” ever become “Big New Energy?”

I think it makes sense to consider new business lines, but only in areas that meet certain economic criteria. ExxonMobil rigorously evaluates all opportunities against internal metrics and wind and solar have not met our requirements. ExxonMobil has invested in research and development in renewables like algae since it has many unique benefits. It relies on available sunlight, but does not require fresh water or arable land and, therefore, does not compete with the world’s food supply. Algae also live by absorbing carbon dioxide, so this technology could also help reduce GHG emissions. If the research is successful, it will not require the complete transformation of existing fuel delivery infrastructure.

Would a globally agreed upon carbon tax be a good thing in ExxonMobil’s view, all things considered, and why?

We believe that the long-term objective of a climate change policy should be to reduce the risk of serious impacts on society and ecosystems, balancing cost-effective mitigation with adaptation, while recognizing the importance of energy to global economic development. When governments are considering policy options, ExxonMobil advocates an approach that ensures a uniform and predictable cost of carbon, allows market prices to drive solutions, maximizes transparency to stakeholders, reduces administrative complexity, promotes global participation, and is easily adjusted to future developments in climate science and policy impacts. We continue to believe a revenue-neutral carbon tax is better able to accommodate these key criteria than alternatives such as cap-and-trade.

Concluding Points

So there you have it. In ExxonMobil’s view, the oil and gas industry is a great place to be the next 25 plus years as the demand for our products surge due to population growth (the industry gets 200,000 new customers every day) and a growing global middle class. The oil and gas we produce fuel human progress and raise living standards. What an excellent career you have chosen or are about to choose!

Even today, however, there are many energy customers not being served: The approximate 1.3 billion without electricity and the approximate 2.6 billion globally who use wood or dung stoves for cooking, which can lead to fatal indoor air pollution. What if we could supply all these too with affordable energy?

More and more, how we produce oil and gas, increasingly matters and delivering a strong health, safety, security, environment and social responsibility performance along with a competitive return on investment is the only way to stay “fit” as an industry and as E&P companies. Going forward, oil and gas will be competing in 3E (Energy, Economics, Environmental performance) with other energy sources competing for market share. We must never stop imagining improved and more sustainable E&P ways of doing it. Maintaining the E&P industry’s overall legitimacy and its social license to operate in local communities all around the globe is the most fundamental assumption underpinning every forward oil and gas scenario. Think about it!