A metric based on a corrective-action-classification system initially appeared to be a valuable leading indicator for management purposes. However, after trial applications, it became clear that, when this metric was used to define performance goals, it had unanticipated consequences that cumulatively and insidiously caused more damage than the accidents it was intended to prevent. Category matching is an upgrade of that original metric and eliminates harmful unintended consequences of corrective-action classifications used alone.

Background

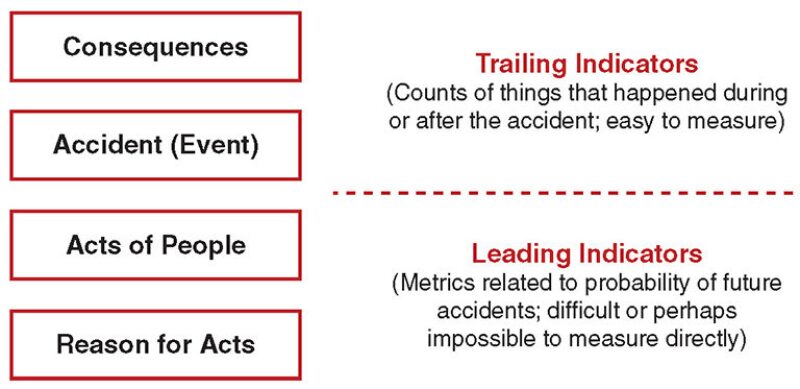

Trailing indicators are by far the most common type of safety statistic. Governments, insurance companies, corporations, and essentially everyone who tracks accidents will record the number and type of injuries, plus the money spent on repairs, machinery replacements, wasted time, or other harmful consequences of accidents. Leading indicators are complicated by the fact that some dangerous acts (e.g., touching high-voltage switchgear) will always produce an accident with severe consequences while other dangerous acts (e.g., running a stop sign) might be repeated hundreds of times without causing an accident. In industrial work situations, no scientifically defensible equation exists where X dangerous acts produce Y accidents with Z fatalities.

As shown in Fig. 1, accidents come in packages with four components. In reverse chronological order, they are (1) consequences, meaning harm (either injury or damage); (2) the accident itself, an unplanned event; (3) an act of people, not intended to produce the accident; and (4) the reason the accident was not anticipated. A broken leg is never an accident. It is an injury and the consequence of an accident. An accident is an unplanned event, and a fall is always an accident regardless of whether it causes injury. The vast majority of accidents cause little or no harm, but confusing an accident with its consequences is a major obstacle to preventing accidents because the target of corrective actions is not clear.

Accident-classification systems tend to describe accident consequences rather than the accident itself. This is important because corrective actions must change what happens before the accident. If a report states that the accident was an eye injury, then a corrective action would prevent the injury by enforcing existing rules about wearing eye protection. That would have no effect at all on preventing the unplanned event that produced the eye injury.

Precisely separating an accident into its component parts, as shown in Fig. 1, is helpful in focusing corrective actions on the right problem. Corrective actions that focus on preventing the accident will be very different from actions focusing on preventing the consequences of that accident.

In the 1980s, a search for meaningful leading indicators led to primitive methods for classifying corrective actions according to their effectiveness. The methods have evolved considerably since then, but the fundamental concepts remain the same. Basic management theory holds that managers change the course of events in three different ways—direct action, supervision, or management.

The original measurement system allocated points for corrective actions given on accident reports. Each stated corrective action was given one, two, or three points if it met definitions of direct action, supervision, or management, respectively. A weighted average of these points reflected the general strength of corrective actions, and two adjustment factors checked if reporting managers were sensitive to near misses and if they actually implemented the corrective actions. The result was an index, a number that was directly related to how well managers identified and solved operational problems.

The problems began when upper management set goals or performance standards on the basis of this index. A management type of corrective action is, in effect, a change in the laws the organization adopts for governing itself. For example, one oil company operating internationally set a standard that required managers to produce an index number that could be attained only by producing rule changes for an unrealistically high percentage of all their recordable accidents. Because nearly all accidents are already covered by rules, either internal or external, that requirement produced a redundancy in rules that increasingly became micromanagerial in nature; and, because rules must be enforced to actually be rules, the requirement amounted to force-feeding the bureaucracy that ultimately suffocates any organization.

Rethinking the Situation

Managers can only change acts of people—either what they do themselves or what their subordinates do. They cannot change physics, chemistry, geology, biology, mathematics, weather, geology, or any natural phenomena. They cannot change the properties of oxygen, fuel, or ignition sources, but they can change the acts of people that bring those fire components together. It follows that no corrective action is possible if an accident cannot somehow be expressed as a consequence of an act of people.

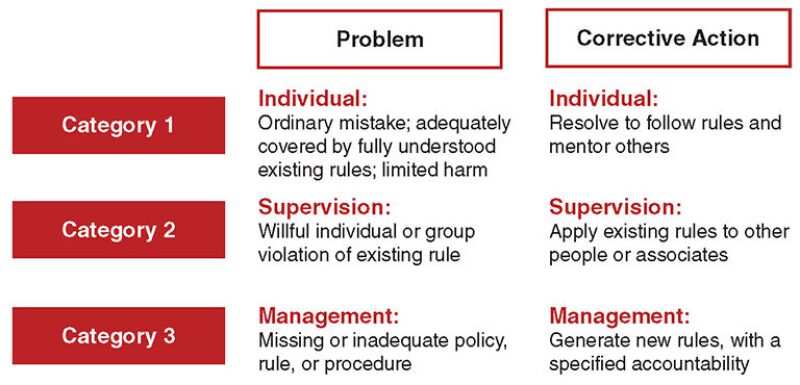

There is an important distinction between safety problems and accident-prevention problems. Both problems and corrective actions can be defined in terms of rules. Category 1 problems are the most common. They involve simple mistakes and violations of standard advice, general rules, or other ordinary good work practices that a person normally follows but simply overlooked, provided that the event produced only minor harm. Examples are spilled coffee, scraped knuckles, bumped elbows, twisted ankles, and similar minor events.

When such an event produces serious harm, it always means there is another problem to identify. For example, if coffee is spilled on delicate electronic equipment and causes major harm, then the issue is not the safety problem of spilled coffee but the accident-prevention problem of enforcing or generating rules keeping the potentially damaging coffee away from the electronic equipment.

Three categories of problems are identified in Fig. 2. Category 1 involves an individual following well-known, fully understood rules. Category 2 involves applying rules to other people. And Category 3 involves missing or inadequate rules.

Defining Corrective Actions

In the past, the term “corrective action” was defined as a plan or a prearranged schedule of events leading to attaining some objective. That overlooked the fact that an action must be a verb, not a noun. “To plan” is a verb, but “a plan” is a noun; and, a plan is simply a list of actions, not the actions themselves. A plan to launch a special satellite may involve hundreds of people arranging tens of thousands of detailed step sequences, but none of those steps are actual actions until the appropriate orders are issued and carried out. A launch plan is not a launch, and a planned corrective action is not an actual corrective action until an order is given. A better definition of a corrective action, therefore, is “Someone with authority and followup responsibility issuing an order to someone with the knowledge, skills, resources, and desire to carry out the order.” That correctly indicates that an action is a verb (“issuing”), instead of incorrectly declaring that an action is a noun (“a schedule”). A useful mnemonic device is that corrective actions must have COATS, meaning they must be in the same Category as the target problem and be an Order issued by someone with Authority specifying Times and Substantiation.

Game Playing

An ongoing problem with safety metrics is their tendency to become meaningless game playing. This happens when a new safety program announces, “Employees will get a reward (positive or negative) if this number is achieved.” That number might be any of the usual trailing indicators, but, whatever it is, there is always an incentive to stretch definitions or slant reports to achieve the target number, sometimes at the expense of accurately identifying and fixing underlying problems.

The great majority of accidents are already covered by policies, standard procedures, ordinary good work practices, or other rules. Generating new rules on top of existing rules has obvious harmful effects. It is also true that the majority of accidents are simple individual mistakes that can never be totally eliminated, and, as long as they have no realistic chance of causing serious harm, they do not merit management-type corrective actions or rule changes. Early applications of the original index required managers to maintain numbers that could be reached only by devising corrective actions meeting definitions of management, as opposed to supervision or direct action. The game then became managers looking for opportunities to report corrective actions and looking for easy actions that would satisfy requirements for being good management. They were soon compelled to report incidents that really did not need corrective actions and to report corrective actions that did not really have any positive benefits.

Category Matching

Most of the damage caused by using corrective-action classifications as a leading indicator can be avoided by simply making sure that both the problem and the corrective action are well-defined and in the same category. This category-matching technique has a potential for becoming yet another game and, therefore, should not be used as a target for entry-level managers, supervisors, or safety advisors. It is useful as an analytical tool for midlevel or upper managers to improve accident reporting and make corrective actions more effective. It should not be kept secret from anyone, but not everyone needs to be involved in either calculating or using this analysis method, just as they do not need to be involved with computing receivable days, return on investment, turnover rates, or any other management metric.

Applying a corrective action of one category to a problem of a different category always causes harm, but it is often subtle and unnoticed. That point can be explained easily through training sessions based on category matching, but it is important to avoid blaming, too. If an individual violates a rule, whether general or specific, it does not necessarily mean culpability or intentional misbehavior. Most drivers can remember instances of being surprised to discover that they were exceeding a speed limit, had forgotten to turn their lights on, or had unintentionally violated some other rule. This is another reason category matching should be reserved for use by people not directly involved in the accident itself or in preparing the accident report.

This article, written by Editorial Manager Adam Wilson, contains highlights of paper SPE 164961, “Unintended Consequences of a Promising Safety-Management Leading Indicator,” by Carl D. Veley, SPE, vMBA Consultants, prepared for the 2013 SPE European HSE Conference and Exhibition, London, 16–18 April. The paper has not been peer reviewed.