Mexico’s historic public tender for its deepwater real estate resulted in the awarding of eight out of 10 blocks on offer. Held last December in Mexico City, the event marked the fourth and final auction of the country’s Round One, which reopened doors to foreign oil and gas investment for the first time since the country’s energy sector was nationalized almost 80 years ago.

The awarded blocks went to 13 companies whose exploration and production operations are expected to generate around USD 34 billion over the next 15 years. The winning bids also committed to drill at least eight deepwater wells.

All four blocks offered in the deepwater Perdido area were awarded, including two to Chinese Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and one to a consortium of Chevron, Pemex, and Inpex—Japan’s largest oil company. An additional four blocks in the Salina Basin were contracted to three different consortiums, including one formed by Statoil, BP, and Total.

Another block encompassing a deepwater discovery known as the Trion field was awarded as a farmout agreement between BHP Billiton and Mexico’s state-owned oil company Pemex. BHP will acquire 60% of the project’s interest under the terms of the contract, which it won through a tie-breaking offer of a USD 624 million cash bonus to Mexico’s petroleum fund. BP was the losing bidder.

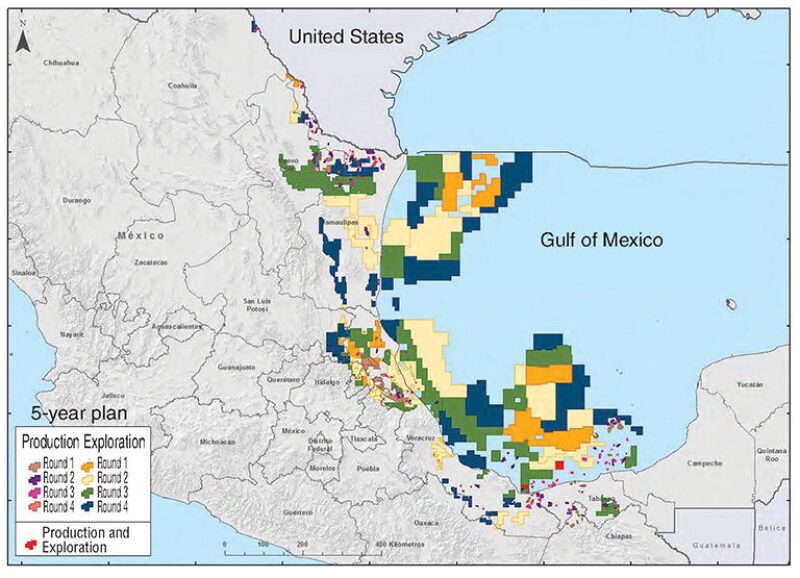

Including the three previous onshore and shallow-water auctions, Mexico has awarded 39 exploration and production contracts to companies from nine foreign countries.

In a press conference following the auction, the government said it expects to receive close to 60% of the combined profits from the eight blocks and the lone farmout. Mexican officials also said they are hoping the deepwater contracts eventually will yield 900,000 B/D of crude, a volume that would help stem the country’s declining production from existing fields. Government officials added that first production from Trion might be reached within 6 years, while it is expected that the other areas will need up to a decade to be developed.

What’s Next?

According to many observers, the production potential that the deep water holds for Mexico was the chief driver behind the country’s sweeping energy reforms that became law in 2013. But now that a number of the prime blocks have been allocated, what comes next?

For the companies that have already signed offshore contracts, their next steps are likely to include the expansion of Mexico’s port facilities to accommodate the arrival of larger deepwater vessels and rigs. Some expect the small port town of Dos Bocas to become a deepwater hub because of its proximity to the southern Salina Basin blocks.

There are fewer port options to the north where the Perdido blocks are located. However, in the area along the Mexico-US maritime border, operators may have the benefit of accessing a subsea pipeline on the US side known as Great White. On the Mexican side of the Gulf, there is no comparable deepwater production infrastructure. That might push operators with the most remote fields to select floating, production, storage, and offloading vessels as their development strategy.

In the meantime, the Mexican government must fill a number of gaps in the country’s health, safety, and environmental rules before deepwater work can move forward on solid regulatory ground. Officials will be further challenged to do all they can to help beef up Mexico’s supply chain capabilities since all of the contracts have a minimum local content rule attached.

There will also be a steep learning curve involved for the regulators. Established by the new reforms less than 3 years ago, Mexico’s National Hydrocarbons Commission has no track record in overseeing exploration and production operations and must balance this role with the need to get production trending upwards as soon as possible.

“The companies will have to walk step by step with the regulator to have a clear understanding of the day-to-day operations. That is the only way the winning companies can achieve the levels of efficiency required to have good profit margins,” explained Gonzalo Monroy, an economist and managing director of the Mexico City-based energy consultancy GMEC.

There are questions, too, regarding whether the Mexican government will stick with the weighting system it used to select the winning bids. In both the first shallow-water auction and the deepwater auction, a number of winning bids were decided by the royalty figure a company or consortium was willing to add on to the government’s minimum requirement.

In the deepwater auction, Statoil submitted a bid with 13% added royalty and a commitment to drill two exploration wells but lost out to a Petronas-led group that bid 22.99% added royalty, with zero well commitments.

Pablo Medina, a Latin American upstream research analyst at Wood Mackenzie, is among those who believe that the government’s preference for royalties runs the risk of awarding contracts to companies that may never drill a well, and therefore, never pay any taxes. “It is not the best idea to worry about how big your slice will be out of a cake that doesn’t yet exist,” he said. “It is much better to make sure that the cake is actually going to be baked.”

After the onshore auction held early last year, the Mexican government announced it would re-tender six blocks after the winning bidders failed to meet the financial requirements. Since the fields were only expected to produce a couple of thousand barrels a day at most, the matter was considered to be a minor wrinkle in an otherwise successful Round One process.

But to prevent overbidding in future rounds, the government will set a maximum for added royalty. Medina said placing a greater emphasis on well commitments would have a similar effect, but noted that the government likely needs to achieve critical mass in terms of the number of awarded contracts before it is willing to take such a step.

Regardless of the royalty issue, Medina is optimistic that the following rounds will attract competitive bids, especially the next deepwater auction. Speaking on the Mexican half of the Gulf of Mexico, he said: “This is still an area where less than 50 exploration wells have been drilled, which is hardly a big number when you compare it with the more than 1,200 [wells] drilled on the US side.”

Reflections on Pemex

The glare of the international spotlight that came with Round One has partly obscured another important story, and that is what this all means for Pemex. After the reforms passed, Pemex was the sole participant in a pre-auction process termed Round Zero, in which 83% of the country’s proven reserves were allocated to the national oil company.

But for the rest, Pemex was told it would have to get in line just like everyone else and join the open market. In Round One, the company chose to participate only in the deepwater auction, a move that surprised few as it reflected Pemex’s well-known desire to revive its languishing deepwater program.

Speaking at an industry event in Houston days after the deepwater auction, Lourdes Melgar, a fellow at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology and Mexico’s former deputy secretary of energy for hydrocarbons, said the auction would not have been considered a success by the government without the deals that Pemex struck with BHP and Chevron.

“One of the reasons why we needed the reform is because there were things that Pemex couldn’t do and couldn’t hire anyone to do, such as in the deep water,” she said, adding that the partnerships are “good news because they mean Pemex will be working with an international oil company and learning how to be a competitive company.”

The reforms did not come soon enough, however, to help Pemex weather its financial storm that has been exasperated by declining production, falling oil prices, and steep debt. Last year, Pemex saw its government-approved budget slashed by 75% and had to issue more than USD 4 billion in bonds as part of a new debt restructuring plan.

Melgar described the financial challenges facing Pemex as “enormous” and lamented that the company remains overstaffed compared with other national oil companies with similar output. Highlighting the ongoing cultural transition that is happening at Pemex, she added that it took quite an effort by corporate leadership to obtain internal acceptance for the farmout of Trion, a deepwater discovery the company made in 2012.

“When you have always been a monopoly, and when you have always made the decisions yourself, there is a certain resistance to sharing the decision making with other people,” she said, adding that the hardest part for Pemex has been in convincing its staff “that we are not going back to the past.”