The US might be exporting even more oil, and commanding higher prices for it, if only it had the right port facilities. A new report from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) found that while US crude shipments continue to rise at an impressive rate since a nearly 40-year government ban was lifted in 2015, exports are constrained by an inability to accommodate Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs).

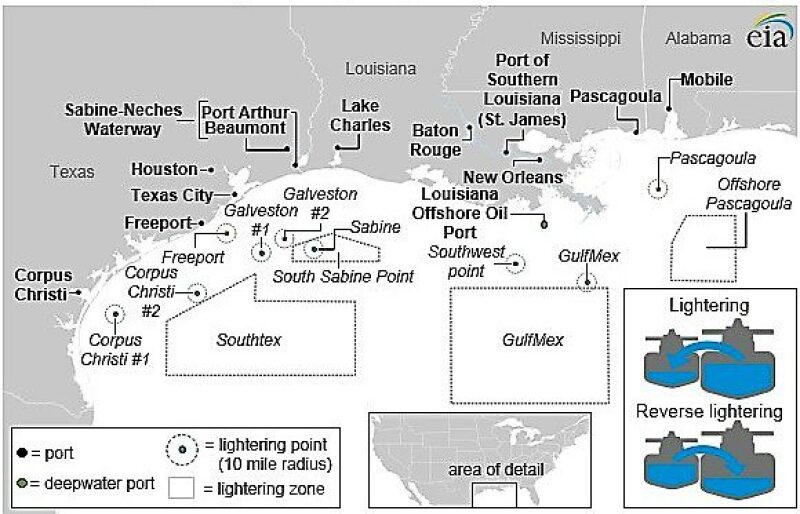

Exports averaged 1.1 million B/D in 2017 and have expanded to 1.6 million B/D in the first half of this year. Crude exports were less than 500,000 B/D in 2016. Almost all of these exports originate from the US Gulf Coast where most loading facilities are located in shallow inland harbors—a factor that has severely limited the use of VLCCs to move oil overseas.

As a result, the world’s second-largest oil producer must rely on smaller tankers that need a wider price spread between US crude and international crude prices to be economically competitive. Because of depth restrictions, most of the country’s ports can handle only the 500,000-barrel capacity AFRAMAX vessels, while a handful of others can take SUEZMAX vessels that may sail with up to 1 million bbl. In comparison, VLCCs can load in excess of 2 million bbl at a time.

The impact that this bottleneck has on sale prices is less severe when the smaller tankers are required to sail short distances. “However, as exports to Asia are a growing share of total US crude oil exports, these costs will become more important,” the EIA report said.

The first VLCC to be loaded with US-produced oil left the Gulf Coast for China in February. This shipment was seen as a major milestone for the domestic industry and was made possible by the conversion of the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP) from an import facility into an export facility early this year. Since then, the LOOP has been used only one other time to load a VLCC but that may pick up with new pipeline projects that aim to deliver crude from Texas to the facility, which sits 18 miles offshore Louisiana.

The significance of the LOOP conversion has already been established. Average weekly US exports have moved above 2 million B/D four times this year, with two of those periods coinciding with the weeks that the VLCCs took cargo from the LOOP. Before the conversion, VLCCs could only be loaded via reverse-lightering; the big downside being the added costs that comes with using multiple vessels.

There are no known plans to construct a terminal similar to the LOOP. However, in May 2017 a 1,093-ft-long VLCC docked near Corpus Christi, Texas at the Oxy Ingleside Energy Center. The occasion marked the first time one of the vessels managed to call on an inland US export facility. It was also an experiment.

Oxy and the Port of Corpus Christi were assessing the feasibility of their plans to dredge the waterway at Ingleside from a low-tide depth of 47 ft to 54 ft—still shy of the 66 ft needed for a fully laden VLCC to navigate. The dredging effort will, however, allow for the VLCCs to be partially filled quayside, with the rest being delivered through reverse lightering. This staged process is expected to provide meaningful savings to exporters using the facility.