Like what you're reading? Sign up for the new JPT Unconventional Insights newsletter to get the latest news to your inbox. |

Profit margins for publicly traded US oil companies rose last year, surpassing the high reached before the 2014 oil price crash, according to a new report by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

The profit gains shown by the 43-company sample are because of rising oil prices, growing production, and tight cost controls. But for many companies, margins are still short of what they need to be.

The day after the EIA report was published in mid-April, Schlumberger predicted “slowing shale oil production growth in North America.” The largest service company predicted a 10% drop in E&P investment in North American onshore plays this year at a time when spending is expected to be rising in other plays around the globe.

Many US operators are spending more cash than they can afford to sustain production at a time when lenders and investors are reluctant to fund companies unable to pay their own way and reward investors.

“In North America land, the higher cost of capital, lower borrowing capacity, and investors looking for increased returns suggest that future E&P investments will likely be at levels dictated by free cash flow,” Paul Kibsgaard, chief executive officer of Schlumberger, said during the company’s quarterly earnings call.

The EIA reported that the 43 publicly traded companies it tracks are generally generating most of the cash needed to pay for exploration and development, but most are coming up short of being able to pay the full cost from operating income.

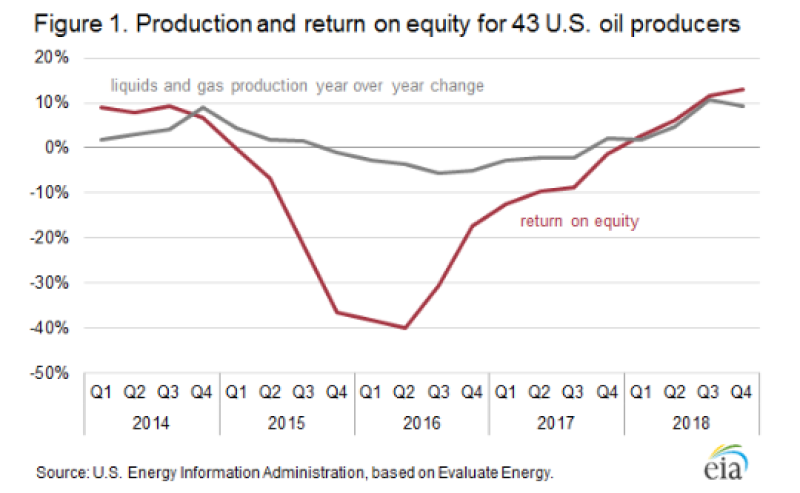

The EIA report looks at earnings from different angles. One is net income, which is looking up. The fast-rising red line in the top chart shows that, as a group, these companies have significantly increased their return on equity—their net income divided by the average shareholder equity (Fig. 1).

But when that analysis focuses on cash flow, they come up short. The cash generated by 80% of the companies is rising over time but is still well below what they need to pay to drill and complete the wells required to sustain production in plays where well output plunges from an early peak.

The late April oil price surge into the mid-$60/bbl range combined with the growing percentage of cash flow paying for drilling suggests that the cash gap may soon close. But simply maintaining production is getting more difficult because output per well is not what it used to be as wells are more closely spaced and development moves away from the best rock.

“As shale matures and operators have to step out to second-tier acreage, it will become increasingly hard to add enough production capacity to replace significant legacy decline volumes, as well as drive new production higher,” said Jeff Miller, chief executive officer of Halliburton. He added that “higher activity and more advanced technology will be needed to maintain flat production levels.”

Good to Be Big

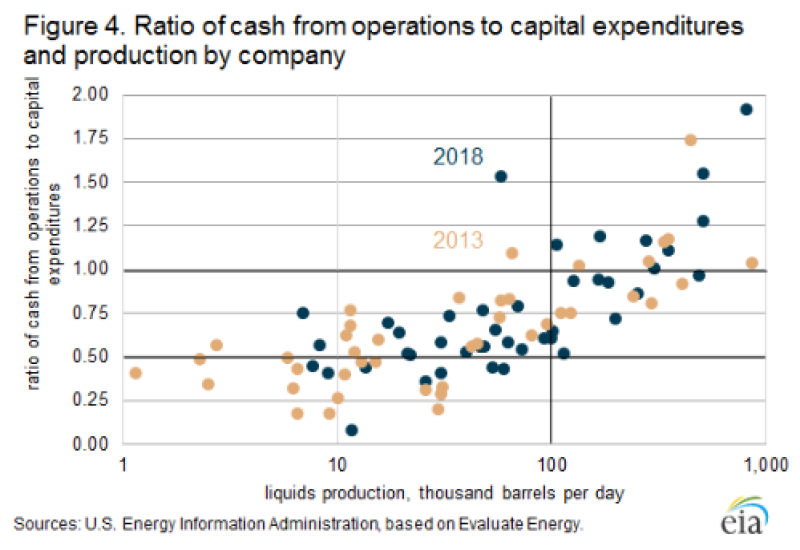

The scattered dots on the chart below make a simple point: big independent oil companies in shale plays are looking far stronger than small ones (Fig. 2). Each dot represents one year of results for an independent oil company in a sample chosen by Jeffrey Barron, an industry economist at the EIA who tracks the performance of companies involved in US unconventional oil plays.

The group, whose production equals one third of the oil and gas produced from US fields, ranges from big players, such as ConocoPhillips and Apache, to small ones such as Jagged Peak Energy and Earthstone Energy.

The key line on the chart is the horizontal bar near the middle labeled 1.00. That is the level where cash from operations is equal to the company’s capital spending.

Any company below that level is paying to drill and complete wells using cash on hand, or money from investors or lenders. Cutting back on drilling to conserve cash is likely to reduce production from wells in plays where rapid declines are the norm.

The dots representing companies that are cash-flow positive are almost all big companies. Based on 2018 results (black dots), there were nine companies at or above the 1.00 line. There was only one company on the high side of the line produced less than 100,000 B/D.

Big companies have the advantage of generating earnings from many types of oil plays. The largest company on the list, with the highest cash-flow-to-spending ratio, is ConocoPhillips. It is strongly committed to shale, reporting that it produces more than 30% of its oil and gas in the lower 48 states. It also has significant conventional assets in Alaska, Europe, and North Africa.

Smaller companies generated considerable more cash to support operations last year than they did back in 2013. In 2018, companies with less than 100,000 B/D of production were clustered in the zone for companies generating from 50-75% of the cash they were spending. In 2013, many were in the 25-50% range.

Barron pointed out that fast-growing young companies go through periods where they are spending a lot of money to develop new products and get them into market. For example, makers of microchips can spend $1 billion before they begin earning money on projects that can generate many times the upfront cost, though there is risk involved.

“It is not necessarily good or bad” to have negative cash flow up front, Barron said. For shale companies, “if it turns out to be that the wells are not so good, perhaps that is not so sustainable.”

Even with rising oil prices, Schlumberger is expecting “a more moderate growth rate in shale plays” because production from new wells is not as great as older ones. Production from closely spaced wells are often hurt by well interference during completions—better known as frac hits.

The challenges presented by unconventional plays have not deterred majors such as Chevron and ExxonMobil from building major positions in the Permian.

Miller described the future of unconventionals as the “industrialization of shale” at a larger scale than today. For Halliburton and Schlumberger, selling advanced technology to the biggest oil and gas companies looks like a promising opportunity.

“We're quite excited about the IOCs taking a bigger position in US land. We work very well with them in the international markets,” said Kibsgaard, who said he anticipates “a more rich technology discussion” going forward in US land.

Rising Oil Prices Matter

Profits improved because revenues rose 31% last year compared with 2017. For the first nine months of the year, the big driver was a 28% rise in the average annual price of West Texas Intermediate oil, magnified by rising production.

When prices dipped during the final quarter, net income still rose due to a spurt of profits from hedging—financial strategies that pay off when prices fall—which more than covered the impact of falling prices.

So far this year prices have been on the way up. Oil prices are now near the 2018 peak, with the benchmark US grade trading for more than $60/bbl in mid-April. Some Permian producers will also benefit from new pipelines coming on line, which will eliminate deep discounts caused by a shortage of pipeline capacity. For operators who lacked pipeline access last year, new lines mean they will be getting the price paid at the Gulf Coast rather than prices $10/bbl or more below the benchmark price because they lack an efficient way to ship the crude to users.

The bottom-line benefit of those increases will depend on the rate of oilfield price inflation. The cost of finding, producing, and transporting a barrel of oil in 2018 was significantly lower than it was in 2013, but it has been rising over the past 4 years. Last year, E&P spending in the companies studied by EIA rose 16% to $23.40/BOE.

Because completion activity in plays such as the Permian is expected to be more sluggish this year, Halliburton said it will cut capital expenditures on its fracturing fleet. “We have sufficient size and scale in the market today and see no reason to invest in growth when it comes at the expense of returns,” Miller said.