Editor’s Note: The oil and gas industry is under public scrutiny like never before on a host of health, safety, and environmental issues. These concerns are already affecting how companies operate and interact with the public. This series is intended to shed light on how the industry is actively confronting these challenges and how it should address them going forward.

Ten years ago, on 20 April 2010, the oil and gas industry suffered a significant human and environmental catastrophe, and a major blow to its reputation. The Deepwater Horizon semisubmersible drilling rig was preparing to temporarily abandon the Macondo well in 5,000 ft of water in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) when the well blew and ignited causing a massive explosion that killed 11 people. The incident resulted in an oil spill of 4 to 5 million bbl (the biggest offshore oil spill in US history) and a cost to the operator (BP) in the order of $60 billion.

This seminal event in the history of the industry caused a moratorium on drilling in the GOM which could have been extended indefinitely but for a comprehensive response by the industry to convince the regulators that the industry could operate safely. Immediately following the incident, the US oil and gas industry assembled four Joint Industry Task Forces (JITFs) to focus on critical areas of GOM activity (American Petroleum Institute, www.api.org); President Obama established a national commission to provide an analysis of the incident and make appropriate recommendations (National Commission on the BP/Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling 2011); and the Secretary of the Interior requested the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) to form a committee to examine probable causes and identify means to avoid future occurrences (National Academies Press 2011).

This article outlines the status of two initiatives: (1) the current National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) program to enhance offshore safety; and (2) a new initiative by regulators and industry to improve the collection of safety data. The article concludes with a summary of the current focus areas to enhance offshore safety. The contribution of the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) to some of these initiatives is described. It is important to note that although the incident occurred in US waters, the lessons learned are applicable to oil and gas operations worldwide, including land operations.

Summary of Lessons Learned From Macondo

|

Key Actions After Macondo

|

The Gulf Research Program

Part of the criminal settlement between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and BP/Transocean was the establishment of an endowment fund of $500 million to be spent over 30 years to conduct science-based programs in three general areas of concern in the GOM and other continental shelf regions: (1) offshore energy system safety; (2) human health; and (3) environmental resources. The management of this fund was awarded to the NASEM, which established a program called “The Gulf Research Program” (GRP). NASEM was selected by the DOJ to administer the program because of its excellent reputation in organizing appropriate experts in the nation to provide advice on critical science and technology issues.

Since its establishment in 2013, the GRP has expended a total of $80 million and has funded seven significant reports and held eight workshops (including oil spill preparedness, human factors, ocean systems, and use of dispersants). Included in the program are grants totaling $60 million for studies on such subjects as human factors, safety performance indicators, ocean systems such as loop currents, community resilience, and the health of the ecosystem. In addition, the GRP has awarded 43 Science Policy Fellowships and 68 Early-Career Research Fellows to help develop a future generation of scientists, engineers, and health professionals for work related to the GOM. In March 2020, the GRP sponsored a simulation exercise of a major offshore incident to test the region’s response capabilities.

A New Initiative To Gather Safety Data

In the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the oil and gas industry, regulators, and other stakeholders recognized the need for increased collaboration and data sharing to augment their ability to identify safety risks and address them before an accident occurs. Accident data have been collected for decades by government agencies, companies, and industry associations such as the American Petroleum Institute (API) and the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP), but much of the data are collected after an incident. Useful proactive data, or leading indicators, have been difficult to obtain.

In 2013, BSEE approached the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) expressing interest in establishing a proactive, near-miss reporting program for the offshore oil and gas industry similar to programs already in place in the transportation sector, particularly aviation.

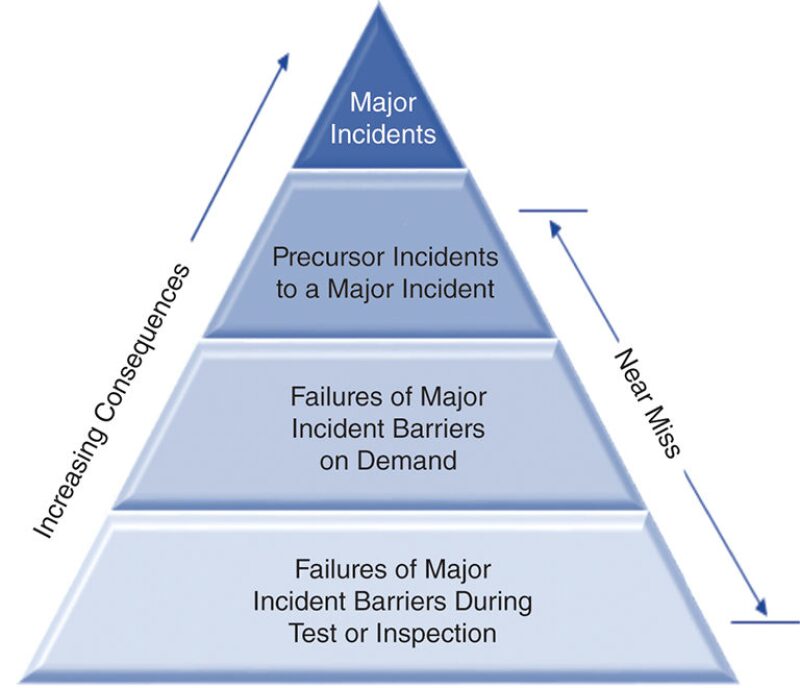

In 2014, BSEE approached the SPE regarding a proposal for industry and government to collaborate on development of a voluntary industrywide data collection framework and management database. The scope of the data with potential learning opportunities ranges from major incidents that result in personnel injuries or fatalities to near-miss events and significant observations of unsafe conditions and/or actions, as depicted in the safety triangle in Fig. 1. Barriers, as referenced in the triangle, are physical, process, or procedural risk controls that seek to prevent unintended events from occurring or escalating.

From 2014 to 2016, BSEE and SPE worked with a team of industry and government representatives to identify potential best practices for the capture and sharing of key learnings from safety and environmental events that were not currently being captured.

The collaboration culminated in BSEE and SPE co-sponsoring a summit in April 2016 to promote a dialogue on what it would take to develop an industrywide safety data management database. The resulting SPE Technical Report (2016) included an action item to pilot a process and database for aggregating and analyzing industry safety data as part of a centralized framework.

This resulted in a pilot program with nine companies called the SafeOCS Industry Safety Database (ISD) managed by BTS. The objective of this program is to capture and aggregate data on a confidential basis so they can be analyzed for trends and learnings with the goal of preventing more serious events. Protection for the data is provided through the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002 (CIPSEA), wherein the source data are protected from subpoena and requests using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

As a federal statistical agency, BTS has considerable data collection and analysis expertise and the statutory authority to protect the confidentiality of the reported information and the reporters. BTS has developed and operated confidential near-miss reporting systems for the railroad and metro transit industries and has a detailed working knowledge of data management systems utilized by other industry sectors.

With successful completion of the SafeOCS ISD pilot effort and proof of concept (SPE Summit 2018), potential next steps to utilize this industrywide safety database include

- Develop new or modified risk controls and support systems, such as training or awareness programs.

- Develop effective communication processes, including dashboards, to share lessons learned, review aggregated results, assess causal factors, network, and discuss potential actions to prevent recurrence and thereby improve safety.

- Develop analytical tools to identify low-frequency events that could indicate the potential for a significant event (e.g., predictive modeling).

Focus Areas To Enhance Safety

Through extensive collaboration among the organizations mentioned in this article, many new initiatives have been developed. The following summarizes some of the key focus areas currently being addressed by industry and regulators to ensure safer offshore operations.

1. Establish and maintain a safety culture.

This includes all the psychological and organizational issues affecting human behavior (National Academies Press 2018; Special Report 321 2016; IOGP Report 453 2018). The intent of an effective safety culture is to embed safety as a deeply held core value in the minds of all workers so that they live and breathe safety. Such a culture is characterized by supportive management, worker empowerment, effective teams, and continuous improvement. It is critical that all contractors and subcontractors should be included in this challenge. This subject was a major focus of a recent series of GRP grants to researchers totaling $7 million.

2. Ensure that all workers have the necessary competence.

The challenge here is continuous learning to achieve, maintain, and ensure the competence of all employees and contractors. Modern methods of training are needed to supplement the traditional classroom and textbook approach. Virtual training sessions using modern cloud-based technology should be developed to make learning convenient for the myriad of contractors who may not be able to attend traditional classroom sessions. A climate of continuous learning by whatever means possible is important.

3. Ensure that all workers have the most recent safety data and instructions for the job.

The industry is overwhelmed with a multitude of recommendations, best practices, and safety alerts to the point that workers have difficulty synthesizing and prioritizing all the data needed when preparing for a task. The challenge for industry management is to make the necessary information available in a concise and useful format. The data should be available on an industrywide open platform so that contractors can work for many different operators with consistent and convenient access to the critical data. The era of digital safety is here.

4. Ensure that significant risks are assessed and mitigated.

Complexity in offshore operations has grown enormously since the time of the first platform out of sight of land in the GOM in 1947 to the current situation characterized by ultradeep water, remotely operated subsea equipment, and complex geotechnical and environmental challenges in deep wells. There are serious engineering challenges involved in designing and operating the sophisticated equipment and in adapting to the variable geotechnical and ocean environments. In addition, there is the ubiquitous potential for human error. The methodology of risk assessment in offshore operations received a big leap in acceptance in Europe after the Piper Alpha incident in the North Sea in 1988 when the “safety case” approach was introduced. Today, there are many risk assessment models available and more are being developed (Vamanu et al. 2016). The main challenges for effective implementation of these models are improved communication between the experts and the users (management, workers, and regulators), improvement in the quality of input data to reduce the range of output, and a commitment on behalf of management to develop and use the models. The application of fail-safe automation, improved sensory instrumentation, and rigorous application of process safety tools and techniques will contribute to mitigating risks.

5. Implement an effective process of collecting and analyzing safety-related data including proactive indicators such as near misses.

While API, IOGP, and OCS have a big inventory of safety incident data, much of the historical data involve description of incidents after they occur (lagging data). Leading or proactive indicators are not as well-collected. A major challenge to capturing industrywide “near-miss” data is protection of confidentiality and company-specific source data. The SafeOCS ISD program is designed to improve the collection, aggregation, and analysis of these proactive data on an industrywide basis in such a manner that protects the confidentiality of the information. Analysis of the data will be enhanced by the development of machine learning and artificial intelligence tools to interrogate the data.

6. Continue cooperation between regulators and operators to enhance safety culture and reduce risks.

The international regulators, in their 2018 forum (International Regulators’ Communiqué 2018), highlighted the importance of data-sharing to improve safety. In the US, BSEE’s Safety Culture Policy Statement encourages operators to focus on hazard identification and risk management and to maintain an open and effective safety communication environment. The regulatory regime should continue to develop a risk-based performance approach as a complement to the traditional prescriptive regulations.

Conclusion

The safety of the people is the highest law. This saying from Cicero in ancient Rome is as appropriate today as it was then. The industry operates by permission of the public. We must instill a safety culture in everyone who works in the oil and gas industry to ensure that safety is a deeply held value because unless we can operate safely, we will not have permission to operate at all. The overall goal is: No harm to people and the environment.

References

American Petroleum Institute. API and Joint Industry Task Force Reports on Offshore Safety Changes.

National Commission on the BP/Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling. 2011. “Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling.”

“Macondo Well Deepwater Horizon Blowout: Lessons for Improving Offshore Drilling Safety.” 2011. National Academies Press.

SPE Technical Report. 2016. “Assessing the Processes, Tools, and Value of Sharing and Learning from Offshore E&P Safety-Related Data,” September.

SPE Summit. 2018. Safer Offshore Energy Systems, 17 August.

Collia, D. and Moreau, R. 2019. “SafeOCS Indusry Safety Data: The Value Proposition for the Oil and Gas Industry. Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center International Symposium, October.

“The Human Factors of Process Safety and Worker Empowerment in the Offshore Oil Industry; Proceedings of a Workshop.” 2018. National Academies Press.

Special Report 321. 2016. “Strengthening the Safety Culture of the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry.” 2016. National Academies Press.

“IOGP Report 453—Safety Leadership in Practice: A Guide for Managers.” 2018.

Vamanu, B., Necci, A., Tarantola S., and Krausmann, E. 2016. “Offshore Risk Assessment.” Joint Research Centre, the European Commission.

International Regulators’ Forum Communiqué. 2018.

Lyn Arscott was the 1988 SPE president. He retired in 2001 as the executive director of the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers. Prior assignments included head of HSE for Chevron Corp. and numerous production management assignments for Chevron/Gulf Oil Co. He is a member of the National Academy of Engineering and a current member of the Advisory Committee for the Gulf Research Program. He holds BS and PhD degrees in mining engineering from the University of Nottingham, UK.

Roland Moreau retired from ExxonMobil in 2014 with 34 years of service during which he held the position of Safety, Security, Health, and Environmental manager for several ExxonMobil business units. He is the 2018 president of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers (AIME), a trustee on the United Engineering Foundation Board, and served two terms on the SPE Board of Directors, first as Technical Director of HSSE-SR and later as vice president of finance. Moreau co-chaired the April 2016 Summit with BSEE referenced herein, and he is currently consulting with BTS on development of an industrywide safety data management framework. He holds a BSME from Worcester Polytechnic Institute and an MBA from Fairleigh Dickinson University.