Someone once said, “It is the thing we least expect that hits us the hardest.” For the offshore oil and gas industry, which has become somewhat accustomed to being hit hard by unforeseen circumstances during its 70-plus-year history, the events of March are unprecedented. Within the space of 3 weeks, coronavirus became a worldwide pandemic; demand—and with it, prices—for oil plummeted; and Saudi Arabia and Russia decided to flood the world market with oil instead of agreeing on an amount by which to curtail production.

For the offshore sector, the latest oil-price rout came just as the market was beginning to look up after some operators had cut costs by more than 50% since 2016, and industry executives and analysts were forecasting annualized revenue growth of 9% from 2019 to 2023.

“We’re only thinking about survival now,” said the chief financial officer of one Scandinavian offshore major after the price of Brent crude dropped 23% in a single session, to $35.01/bbl. (At the time of writing, Brent was $32.62.)

Deutsche Bank analyst Chris Snyder said his company was exposed because it was banking on an acceleration in deepwater drilling. “This is a very unlikely proposition in the current landscape,” he told the Wall Street Journal on 9 March. The Saudi policy would be especially negative for deepwater development, Snyder explained, because developing these projects requires significant upfront capital expenditure (capex) and, thus, confidence in the commodity price outlook.

As this article goes to press, the flooding of the world’s total oil production with an estimated extra 2.5 million B/D looms, leading toward one of the biggest oil supply gluts the world has ever seen. Rystad Energy predicts that the negative impact of COVID-19 on oil demand could amount to between 12 million and 16 million B/D over the next months as more people will have to be quarantined for a longer period, causing an even more dramatic impact on oil demand through the year.

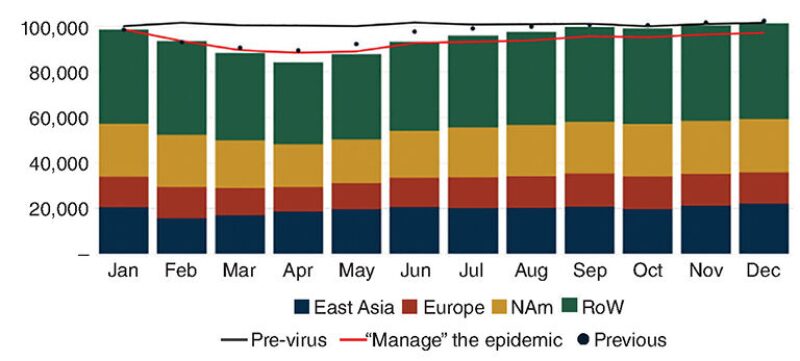

In its final March forecast for oil demand, Rystad projected a decrease of 4.9% for 2020, or 4.9 million B/D year-on-year, from a yearly total of 99.9 million B/D in 2019 to 95.0 million B/D in 2020. The consultancy said it expected the month of April to take the biggest hit, with demand for oil falling by nearly 16 million B/D year-on-year, almost a 16% drop (Fig. 1).

January Optimism

As 2020 opened, the offshore sector was celebrating 2019 as its third-best year on record, with free cash flow reaching nearly $90 billion. Offshore regions had dominated the highest volume of new resource discoveries since 2015. Breakevens for pre-final-investment-decision (FID) deepwater projects had fallen to an average of $50/bbl, and increased use of phasing and subsea tiebacks had cut time to first production. Re-thinking “business as usual” and bringing costs down had led to a resurgence in activity in 2019 and estimates of a moderate rise of 4–7% in 2020 exploration activity over 2019. The optimism was heightened by the expectation that nearly $60 billion of greenfield offshore commitments for 2020 would be for fields with breakeven prices below $40/bbl.

BP’s deepwater Orca gas field offshore Mauritania was the largest single discovery of 2019, with an estimated 1.3 billion BOE. Offshore Guyana, ExxonMobil had added four discoveries in its Stabroek block, while Tullow Oil’s Jethro and Joe exploration wells established a working system in the Orinduik block. Other key offshore discoveries included Total’s Brulpadda off South Africa, ExxonMobil’s Glaucus off southern Cyprus, CNOOC’s Glengorm in the UK North Sea, and Equinor’s Sputnik in the Norwegian Barents Sea.

Rohit Patel, a senior analyst with Rystad, predicted in 2019 that Africa would see the highest increase in licensing activity in 2020, along with several smaller countries in Southeast Asia and the Americas. He observed that operators in Northwest Europe, Africa, and Asia Pacific had been exploring actively in frontier areas in 2019 and said, “The continued benefits of higher cash flows, efficiency gains, and cost reductions are expected to encourage operators to run high-risk frontier exploration campaigns in 2020.”

Another analyst remarked, “Near-field exploration has been a particular standout in mature markets. The range of independents working in the US Gulf have had a series of successes that should support the brownfield tieback market for some time.”

A New Reality

Everything changed in March. The coronavirus became a global pandemic, financial markets crashed, and Saudi Arabia and Russia quit negotiating. On 11 March, Espen Erlingsen, Rystad’s head of upstream research, said, “Without OPEC+ the global oil market has lost its regulator, and now only market mechanisms can dictate the balance between supply and demand.” Since then, market mechanisms have been in chaos, and supply is growing as demand and prices plummet.

With global demand now “in freefall” according to International Energy Agency (IEA) head Fatih Birol, survival has replaced optimism throughout the offshore industry as it has for the entire oil and gas industry, and indeed, the global economy.

“Companies will turn every stone and cancel every single nonrevenue-generating activity,” said Audun Martinsen, Rystad’s head of oilfield service research. Rystad predicted that total industry spending on E&P will be cut by $100 billion this year and another $150 billion in 2021 if prices remain around $30/bbl.

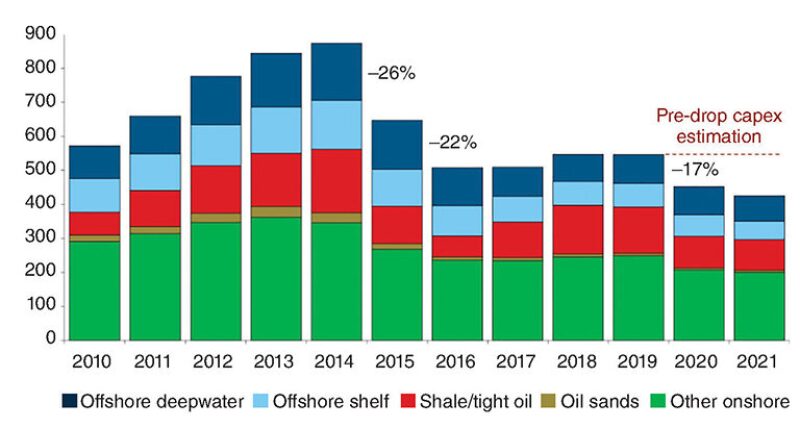

According to Martinsen, the offshore market will be better off than shale and some others in 2020 because it is largely driven by actions and field sanctions from previous years, and so will take more time to react to the market. For example, of the $100-billion decline that is expected in the oilfield services market in 2020, shale will account for $70 billion (Fig. 2).

Martinsen believes the offshore decline in 2020 will be primarily in exploration activities. “Some companies will try to cancel rigs, but if they can’t, they will move from exploration to infill drilling, to build production and boost profits in a shorter time,” said Martinsen. Only a handful of projects are likely to be sanctioned in 2020, although some companies will go ahead with signature projects with short and clear paybacks. Floating rigs will fall to 22 units, and the seismic market will decline 60%. Subsea business, being driven by 3 years of growth on trees awarded, will maintain flat revenue in 2020 in the base case. Offshore supply vessels will be very hard hit.

“I believe there will be more consolidation than bankruptcies for offshore,” said Martinsen. “Companies that have money may try to spend it in a downturn. But, ‘big oils’ are also facing uncertainty.”

More than a million jobs in the oilfield service industry are likely to be cut in 2020, with shale again bearing the brunt. Rystad predicts that the offshore workforce is likely to be reduced by a total of 19% as low oil prices halt most of the exploration work and maintenance, modifications, and operations projects in the second half of the year, and the fear of a COVID-19 outbreak on offshore platforms and yards forces E&P companies and contractors to suspend activities.

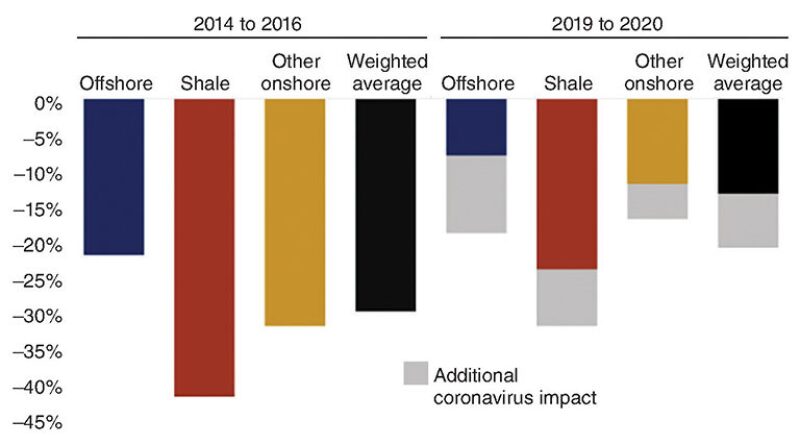

“Low oil prices are likely to persist in 2021 and could lead to further workforce reductions. But as we move into the second half of 2021, with better market fundamentals and a fading COVID‑19, recruitment is likely to pick up in the shale sector; from 2022 it will also kick off in the offshore sector,” said Martinsen (Fig. 3).

Looking at the Specifics

More than three-quarters of global deepwater production is operated by eight companies—BP, Chevron, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Petrobras, Shell, and Total. Collectively, they operate 23 of the top 25 deepwater assets. Here is a brief look at where they stood as of the end of March.

- BP will reduce spending and has reaffirmed its ambition to radically reshape the company by shifting to renewable energy and slashing carbon emissions to net zero by 2050.

- Chevron is cutting capital spending by 20% to $16 billion—its lowest spending level since 2005—and is also halting its buyback program.

- Eni will reduce capex in 2020 by approximately $2.16 billion—or 25%—and operating expense (opex) by approximately $432 million. The cuts are related mainly to upstream activities, particularly production optimization and new projects scheduled to start in the short term.

- Equinor plans to cut investments, exploration drilling, and operating costs by approximately $3 billion, to $8.5 billion. Having already suspended a $5-billion share buyback program, the company said it would postpone US onshore drilling to allow its operations to be cash-flow neutral in 2020 at an average oil price of approximately $25/bbl.

- ExxonMobil said it will cut capital spending by 30% in 2020 but will remain committed to Guyana.

- Petrobras planned to cut a total of 100,000 B/D of oil production by the end of March; reduce planned investments for 2020 from $12 billion to $ 8.5 billion based mainly on postponements of exploratory activities, interconnection of wells, and construction of production and refining facilities, and of the devaluation of the real against the US dollar; accelerate reduction of opex with an additional decrease of $2 billion, focusing on mothballing shallow-water platforms with higher lifting cost per barrel; and lower costs with well interventions and optimization of production logistics.

- Shell will cut operating costs by up to $4 billion over the next 12 months and reduce planned spending by $5 billion in 2020. The company is also abandoning a $1-billion share buyback and plans to trim its 2020 capex by a minimum of $5 billion from the past projection of $25 billion, along with material reductions in working capital.

- Total will implement capex cuts of more than $3 billion, or 20%—mainly in the form of short-cycle flexible capex—limiting 2020 net investments to less than $15 billion. The company also plans $800 million of operating savings vs. the $300 million previously planned.

Regional Reductions

Commenting on the near-term impact of low demand and prices on offshore developments, Gregory Brown of Maritime Strategies International said, “We think that West African work, which already had questionable economics, looks particularly at risk, while investments in Brazil could be scaled back.

“Middle Eastern offshore activity looks to be more resilient. The immediate impact could be that in the absence of work elsewhere, these tenders could become even more competitive,” he said.

Africa—Many of Africa’s largest planned offshore projects will most likely be delayed. In most cases, according to Rystad, the top upcoming final investment decisions (FIDs) in Africa have a breakeven crude price of more than $45/bbl, with some closer to $60. If these projects do not go ahead as planned, this will likely cause the continent’s liquids production to decline for much of the 2020s, with a major impact on some energy-reliant state budgets.

Australia—Like Southeast Asia, activity is expected to be curtailed. Woodside Energy has cut its forecast overall expenditure for 2020 by around 50%, to $2.4 billion, and further reductions may follow. Woodside will push back FIDs for the Scarborough gas project off Western Australia and Pluto LNG Train 2 on the North West Shelf to 2021. The offshore Browse gas project will be deferred. However, investments will continue in the Sangomar Phase 1 development off Senegal, and the Pyxis Hub and Julimar-Brunello Phase 2 off Western Australia.

Eastern Mediterranean—Because it is mostly gas, this region won’t be impacted as long as the long-term outlook remains intact, said Rystad.

Gulf of Mexico—Rystad predicts that most activities will be curtailed, and some operations shut down, although a handful of projects from Shell and BP will go ahead as planned. The March lease sale saw 84 bids from 22 participating companies—60% of them, majors—with high bids totaling $93 million—roughly half the amount of the August 2019 lease sale. Bidding on leases close to existing infrastructure was a recurring theme.

Guyana—With prodigious fields producing relatively low-carbon-intensity light crudes and breakeven costs of under $30/bbl, production should continue, and Hess believes the ExxonMobil-Hess-CNOOC partnership will be self-funding within a couple of years.

North Sea—Neivan Boroujerdi, principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie’s North Sea upstream team, said the North Sea can survive in the short term. “Cost reductions achieved during the last downturn mean 95% of onstream production is ‘in the money’ at $30/bbl,” he said, and also predicted that close to a quarter of the fields will run at a loss. “Most FIDs for 2020 are off the table,” he continued. “At current prices, nearly two-thirds of development spend could be wiped from our forecast over the next 5 years.”

The UK, despite hitting its 2105 cost-reduction target and leading the world’s offshore markets in cost reduction, still has the highest opex per barrel of all major offshore regions because of smaller field size, a fragmented operator landscape, a more mature continental shelf, and a higher number of personnel on board per produced barrel, according to Rystad. As a result, annual investment could fall below $1 billion by 2024, making the threat of stranded assets real.

Norway’s outlook is quite different. “More than 60% of investments come from locally focused players with strong balance sheets,” said Boroujerdi. The giant Johan Sverdrup field, which came on stream 2 months ahead of schedule, at two-thirds of anticipated costs and with notably reduced carbon footprint, is expected to drive the future of oil production in Western Europe. Along with Johan Castberg, it is also the field with the lowest breakeven price—approximately $25/bbl, according to Rystad. The challenge for these two fields, said Martinsen, is that they are dependent on modules and topsides coming from Europe and Asia, with many built in China, Singapore, and South Korea. The impact of the coronavirus on supply chains has caused delays of 3 months, and is likely to cause additional delays of 6 to 9 months. Berislav Gaso, upstream executive vice president at Hungary’s MOI, sees Norway as the last country standing in terms of hydrocarbon production in Europe. “It’s a legitimate ambition to be present there if you’re an integrated oil and gas company from Europe,” he said.

How Low Can We Go?

How low can the oil price go before different sources of production become uneconomic? Where are production shut-ins most likely? Using its Lens database, Wood Mackenzie calculated global short-run marginal costs (SRMC)—that is, operating costs plus taxes and royalties) for current production. SRMC represents the price required for existing production to remain profitable. It excludes capital costs required to sustain, or grow, production and is the best way to consider production at risk of shut-in from an economic perspective, said the consultancy.

“In the last downturn virtually no out-of-the-money production was shut in,” according to WoodMac. But, the firm pointed out, in 2015 and 2016, prices only dipped below $45/bbl for a year, and below $35 for one quarter.

Saudi Arabia’s conventional oil has the lowest production costs, with a weighted-average SRMC of $4/bbl. Russia is also at the low end of the marginal cost curve at $10/bbl on the same basis.

“There is no precedent for the scale of potential shut-ins for today’s asset classes if there is a prolonged period of low prices. The industry’s ability to keep higher-cost barrels flowing will be severely tested,” said WoodMac. According to the firm, conventional production, with a global weighted-average onshore post-tax SRMC at $9/bbl, is least at risk. Offshore shelf assets, at $10, are at slightly more risk than conventional onshore. This compares to global tight oil’s $12, deepwater’s $13, and heavy oil’s $28.

No one knows what will come next. “True recession may send OPEC+ back to the negotiating table, but not enough to bring prices above $40–$45/bbl. We’ll know much more in 3 months’ time,” said Martinsen.

“I do believe in an upswing,” said Gaso. “I think it’s quite ugly times ahead of us, and we need to get prepared for a longer period of sustained low oil prices. But in the end, I think the world will return to normalcy again. How long that’s going to take nobody knows, but I do believe that the industry as such will survive.”

Until then, maybe we should remember some wise words from renowned American physicist and one of the fathers of string theory, Leonard Susskind: “Unforeseen surprises are the rule in science, not the exception. Stuff happens.”