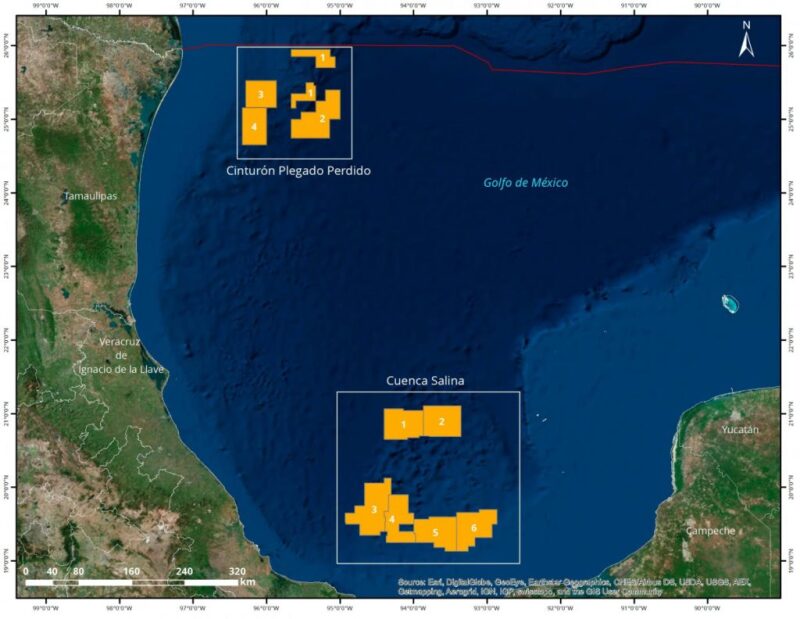

Mexico’s historic public tender for its deepwater real estate resulted in the awarding of eight out of 10 blocks on offer. Held Monday in Mexico City, the event marked the fourth and final tender of the country’s Round One process that has reopened the doors to foreign oil and gas firms for the first time since the energy sector was nationalized almost 80 years ago.

A total of 13 companies were awarded rights to explore and produce from offshore fields in the Gulf of Mexico. The winning bids also committed to drill at least eight deepwater wells.

All four blocks on offer in the Perdido area were awarded, including two that went to the Chinese Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and one to a consortium of Chevron, Pemex, and Inpex—Japan’s largest oil company. An additional four blocks were awarded in the Salina Basin to three different consortiums including one formed by Statoil, BP, and Total.

Another block encompassing a deepwater discovery known as the Trion field was awarded to Australia’s BHP Billiton as a joint-development project with Mexico’s state-owned oil company Pemex. Including the previous onshore and shallow water auctions, Mexico has now awarded 39 exploration and production contracts.

More than half of the winning bids during the deepwater tender exceeded the minimum royalty of 7.5% by double-digit figures. This has been something of a trend throughout Round One in which some companies, mostly those with no experience in the region, have submitted aggressive bids in order to secure a position in this emerging arena.

| Area | Winning Bidder | Added Royalty | Added Local Investment | Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perdido | ||||

| Area 1 | China Offshore Oil Corporation | 17% | 1.5% | China |

| Area 2 | Total, ExxonMobil | 5% | 1.5% | France, USA |

| Area 3 | Chevron, Pemex, Inpex | 7.44% | 0.0% | USA, Mexico, Japan |

| Area 4 | China Offshore Oil Corporation | 15.01% | 1% | China |

| Salina Basin | ||||

| Area 1 | Statoil, BP, Total | 10% | 1% | Norway, UK, France |

| Area 2 | NO BIDS | |||

| Area 3 | Statoil, BP, Total | 10% | 1% | Norway, UK, France |

| Area 4 | Petronas Carigali, Sierra | 22.99% | 0.0% | Malaysia, Mexico |

| Area 5 | Murphy Oil, Ophir, Petronas Carigali, Sierra | 26.91% | 1% | US, UK, Malaysia, Mexico |

| Area 6 | NO BIDS | |||

Malaysia’s Petronas Carigali and Mexican independent Sierra Oil and Gas partnered in a winning bid that promised an additional 22.99% royalty. For its two winning bids, CNOOC offered added royalties of 15% and 17%. The highest bid of the day came from a consortium led by US operator Murphy Oil, which won a block with an added royalty figure of almost 27%—putting the total government take at about 34.5%.

The government estimates that it will collect almost 60% of the potential profits to be made from the eight blocks and the lone joint-development contract. “This is noteworthy because these are the fields that have more risk … and more geologic complexity than the ones that have been bid on so far,” noted Juan Carlos Zepeda, the president commissioner of the country’s regulator, the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH).

Mexican officials also said they are hoping the deepwater contracts will eventually yield 900,000 B/D of crude; a volume that would help stem the country’s declining production from existing fields. They are also hopeful that production from the Trion field could start up within 6 years, while it is expected that the other areas could take as long as a decade to achieve first oil.

What’s Next?

According to many observers, the production potential that the deepwater holds for Mexico was the chief driver behind the country’s sweeping energy reforms that became law in 2013. But now that most of the prime blocks have been allocated, what comes next?

For starters, Mexican officials must fill a number of gaps in their safety and environmental rules before deepwater work can move forward on a solid regulatory ground. There will also be a steep learning curve involved for the regulators. Established by the new reforms less than 3 years ago, the CNH has no track record in overseeing exploration and production operations and must balance this role with the need to get production going as soon as possible.

“The companies will have to walk step by step with the regulator to have a clear understanding of the day-to-day operations. That’s the only way the winning companies can achieve the levels of efficiency required to have good profit margins,” explained Gonzalo Monroy, an economist and managing director of the Mexico City-based energy consultancy GMEC.

There is a similar need to establish strong supply chains to ensure the future projects stay on schedule and on budget. Current trade laws will aid the effort by offering oil companies the unrestricted ability to import specialized subsea equipment made in the US.

Monroy said such access gives Mexico’s deepwater sector a competitive edge on the world stage, but noted this is subject to change pending the policy direction of the incoming US presidential administration, which during the campaign season adopted strong anti-trade positions in regards to Mexico.

Infrastructure Needed

The other missing piece to Mexico’s deepwater puzzle is infrastructure, both offshore and onshore. For the Perdido blocks, and particularly the one located right along the maritime border, there is a pipeline flowing on the US side known as the Great White, to which new production may be tied into.

But on the Mexican side, there is almost no deepwater infrastructure, which means for the more distant areas, the best development strategy may be to use floating, production, storage, and offloading vessels.

Deepwater port facilities are also lacking in Mexico and this has been highlighted as a key constraint facing the new entrants. Since there is no framework in place for support vessels to be used from the US, the nearest port that could be used by deepwater operators is in Tampico. The problem, though, is that the port there is positioned nearly 300 miles from the primary operating areas of Perdido—a far greater distance than most other deepwater developments around the world deal with.

In the southern Salina Blocks, less may be known about the geology, but these areas are much closer to port facilities that could potentially support deepwater projects. However, deepwater operators may be challenged in using Mexico’s traditional offshore hub, Ciudad del Carmen, given that its port facility is already highly congested and its shallow depths are not suitable for deepwater vessels.

A port near the small town of Dos Bocas has been identified as one of the most likely candidates for a deepwater shore base, but it too is in need of an expansion in order to handle dynamically positioned workboats and large drilling rigs. The town also has no international airport or many hotel rooms.