With oil prices slowly recovering from the downturn, exploration and production (E&P) companies are being forced to look at smaller capital investments to help maintain financial stability. Instead of taking chances on high-risk, long-cycle megaprojects, they’re devoting a larger percentage of their capital expenditure (capex) on smaller, short-cycle projects. While these projects may not carry the potential for massive returns that megaprojects carry, short-cycle projects allow owners and operators to stay financially stable in the low-price environment while preserving the production infrastructure and capacities needed to expand quickly when oil prices improve.

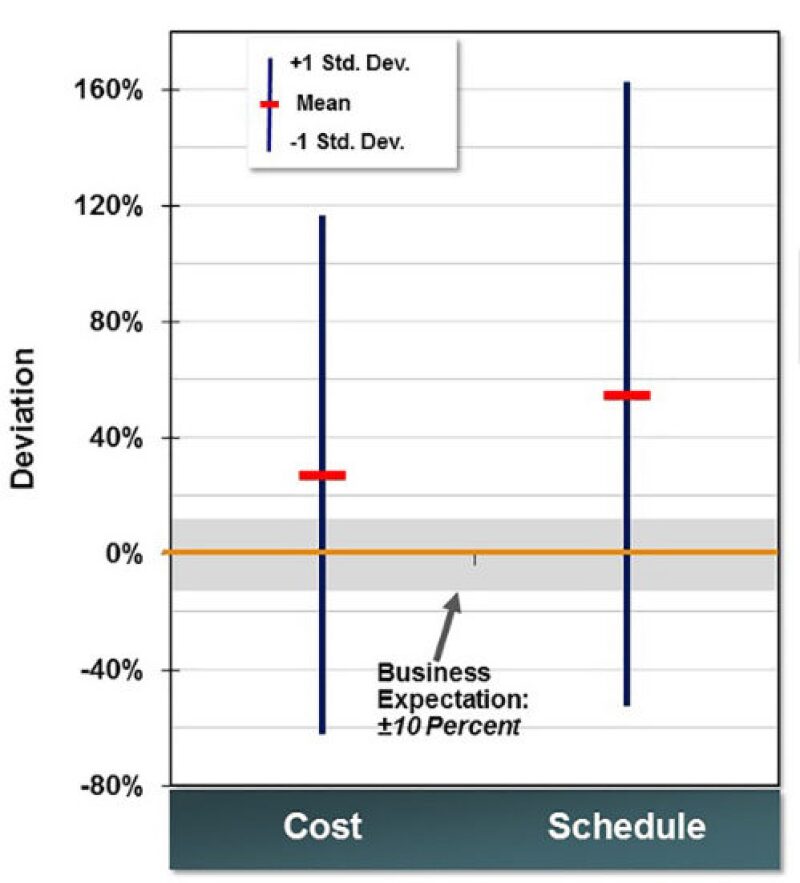

Associate project analyst Ifunanya Onwumere at Independent Project Analysis (IPA) wrote in a recent article that, even though short-cycle projects are not a new concept in E&P, owner companies are investing larger portions of their portfolios in them as oil prices remain around USD 50–55/bbl. However, because the industry has spent much of the last decade focused on megaprojects, Owunmere claimed that a pivot to a portfolio heavy in short-cycle projects may be difficult for owners and operators without a holistic approach. IPA determined that E&P short-cycle projects are overrunning their cost targets by as much as 120%, and schedule performance is worse (Fig. 1).

Katherine Marusin, manager of IPA’s site and sustaining capital business sector, said that short-cycle projects are critical for owner-operators in the low oil price environment.

“I think what people sometimes fail to recognize in the E&P sector is that sometimes their future is populated with projects that are measured in the millions and not the billions,” Marusin said. “The fact that they’ve really ignored a lot of the smaller efforts that would make up anywhere from 40% to 80% of their project portfolios means that they don’t really have the competency to do these things well and they simply don’t know how to do them well. Because it’s the bulk of what you do and what you will be doing, I would argue that they are of increasing importance and were pretty important to begin with.”

Marusin said the industry needs to pay more attention to the impact short-cycle projects can have on a portfolio, but also that she was encouraged by the questions operators are asking IPA about how they can improve on this. She said the larger operators are leading the charge, in part because they can afford more sophisticated forecasting, giving them a better sense of how smaller projects can fit into their financial future.

“On some of the larger companies’ megaprojects, they’ve seen that this is a pretty foolproof formula that’s being employed. So, if we can translate that down to the shorter-cycle projects, we’re likely to save some money and be a little healthier,” she said.

In working with operators, IPA found that three overarching business decisions can drive the success, or the volatility, of the smaller short-cycle return projects:

- The criteria companies use to differentiate and separate short-cycle, sustaining capital projects from major projects

- The ways in which companies modify their work processes to specifically cater to short-cycle projects

- The ways in which companies evolve their organizational structures and approaches to support a portfolio tilted toward short-cycle projects

Short-Cycle Complexities

As they are generally smaller in size and scope, operators often categorize their short-cycle projects as less complex and easier to execute. Onwumere claimed that this was a misstep because, like megaprojects, short-cycle projects routinely contain unique complexities that must be considered and worked out during the front-end planning and development phases. If ignored, these complexities could erode a company’s profitability. Onwumere said that companies should create a holistic complexity-based ranking for differentiating between “major” and “non-major” projects, organizing and executing the non-major projects with a necessary amount of attention and discipline.

Marusin said that, while they may be unique in some fashion, operators may face complexity issues with a short-cycle project similar to those in a megaproject, particularly with regards to regional barriers such as local content requirements, language barriers, and other cultural differences.

“If it’s hard to do a large project someplace because of regional considerations, it’s going to be hard to do a short-cycle project there,” she said. “Some of the times you have this gung-ho optimism, but for the smaller projects companies will say, ‘Well, of course we can get it done.’ So you take it for granted. You think, even though we know we’re a little short-staffed, we’re pretty confident that we can make do with what we’ve got and do it. It’s a little different driver for some optimism and disappointment.”

Inadequate work processes and organizational structures may compound the problems that stem from a short-cycle project’s complexities. Onwumere said that these issues often result from a lack of critical resources companies have when making project categorization decisions. Because operators oversimplify work processes and rely on lean project teams to handle tasks presumed to be simpler because of the smaller scale of the projects themselves, those teams must make do without vital functions. Onwumere stated that overreliance on simplified teams for complex projects leads to chaos.

Marusin said the lack of resources often boils down to staffing. Short-cycle projects are unstaffed in project controls, namely in estimation and scheduling. For these tasks, larger operators may rely heavily on contractor organizations that are not familiar with the operator’s procedures, or its organizational culture.

Also, operators still dealing with depleted full-time rosters may designate their less experienced project personnel (engineers, project managers, construction managers, and other control staff) to their smaller projects because of a perceived lack of complexity. Marusin said this is not necessarily a bad thing. Organizations within the onshore and offshore sectors look at smaller projects as what she termed a “refuge of talent” for younger staffers where they are trained in how to manage larger projects, and such investments in talent force them to run these projects more efficiently.

Despite this investment, Marusin said companies may benefit from using experienced staffers on smaller projects to help navigate these complexities.

“I think that this is an industry that would benefit from having people who have experience in managing project portfolios,” she said. “It gets completely out of whack, projects get neglected, and we need the folks who have the ability to throw up the flag and say, hey, we need to get these things done because they have to get done for us to stay in business. We can’t neglect them for something sexier.”

Finding the proper balance in a system designed for delivering short-cycle projects can be difficult for operators. Marusin said the keys for companies looking to reach this balance in a portfolio are prioritizing the objectives they wish to achieve with their projects and acknowledging the capabilities within their organizational structures. This requires taking several considerations into account, from project classification (for example, growth-type projects vs. regulatory maintenance) to facility requirements, equipment, and even a company’s long-term goals.

“I think sometimes portfolios get assembled and we’re sort of blind to our abilities and the resources that are available to actually get the work done. So you have ambitious portfolios where you say there’s no way an organization is going to get through that. That’s the one thing when it comes to striking the right balance. You have to be realistic about what you can actually do and what you should be doing,” she said.

Unconventionals

The unconventional sector is an area where owner-operators are looking for immediate returns on smaller projects.

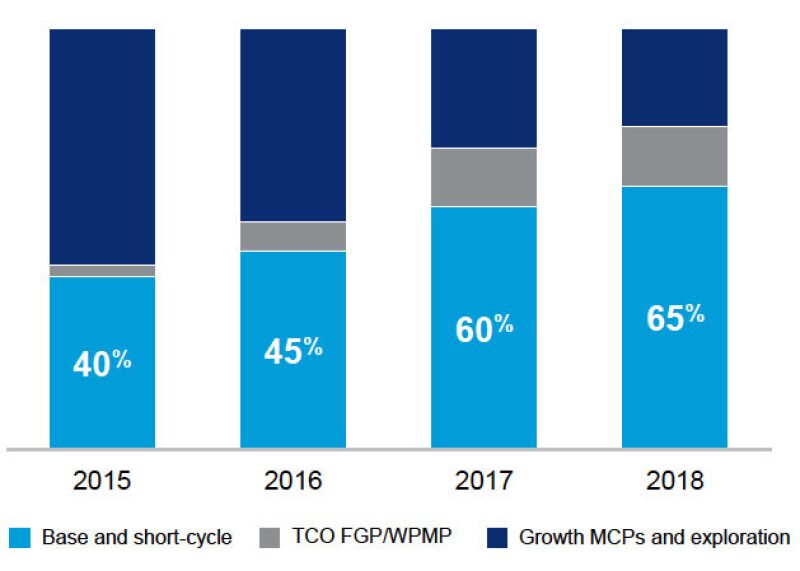

In the wake of an USD 11.6 billion drop in capital and a 24% decrease in 2016 capex, Chevron outlined plans to target short-cycle projects, with an increase in spending on shale gas, tight oil, and brownfield projects, and a decrease in spending on major capital projects in the offshore sector (Fig. 2).

Most of its focus will be on unconventionals. The company holds approximately 1,300 drilling locations in the Permian Basin, estimating that, if oil prices stay at USD 50/bbl, it needs to operate 4,000 of those locations to turn a profit.

Chevron chief executive officer (CEO) John Watson said in a January earnings conference call that he would not be surprised to see unconventional activity make up 25% of Chevron’s production by the mid-2020s.

“We added to our resource base 500 million barrels [in 2016] in the Permian without spending any money,” Watson said. “And we did that by watching what offset operators have done. By being a little bit behind others we have been able to learn and that has helped us prioritize the spend that we are doing.”

Chevron still has larger projects on the docket in the immediate future. Despite several delays, the company still expects to start up Big Foot, an extended tension-leg platform in the US Gulf of Mexico, in 2018. Last year it approved a USD 37 billion expansion of the Tengiz oil field in the Caspian Sea, and the company spent more than USD 80 billion on a pair of liquefied natural gas projects in Australia: Gorgon, which started up in March 2016, and Wheatstone, which is expected to start up this year.

Despite these investments in major capital projects, Watson said Chevron has always sought to maintain flexibility in its budget, and that flexibility will allow it to develop more short-cycle projects moving forward.

“In the early part of the decade I was very clear we were heading into a period where we had significant major capital projects. We were going to keep some capacity on the balance sheet. … Now, we didn’t expect to see the drop in prices as big as we saw, but it proved to be pretty wise to keep that capacity on the balance sheet. Now we are in a different period. We do have the Tengiz project, but I don’t see anything like a Gorgon, Wheatstone, or Tengiz that is in our future. We could see a deepwater development, but none of those that are of that same magnitude,” Watson said.

ConocoPhillips has also shifted away from its deepwater projects to focus on shale production, primarily in the Bakken where it holds approximately 620,000 net acres. In a presentation given at the Goldman Sachs Energy Conference in January, the company projected a production level of 7 billion BOE from unconventionals, citing them as a large and flexible source of short-cycle growth with low execution risk.

“Our margins should improve as we allocate more capex to high-return, short-cycle investments,” ConocoPhillips chairman and CEO Ryan Lance said in a Q4 2016 earnings call. “We’ve guided lower adjusted operating costs, exploration costs, and [depreciation, depletion, and amortization] vs. 2016 and we think these improvements are sustainable.”

Marusin said IPA has observed an increase in E&P spending in the unconventional sphere. While she warned that companies who have neglected their short-cycle projects should not view unconventionals as a panacea for their financial ills, companies with established good practices and a track record of efficiency in managing larger projects should be effective in managing these projects.

“Within the unconventional space, I think there are folks who have moved in from downstream and manufacturing, and they’re bringing good practices that were learned from that side of things. I think the same thing is true for some of the other E&P organizations, offshore, and more conventional sites. There are companies that are bringing the competencies from other industry spheres into the unconventional world,” Marusin said.