The executive role in delivering capital projects is often underestimated. Executives provide direction, supervision, and support to the teams responsible for developing and executing capital projects.

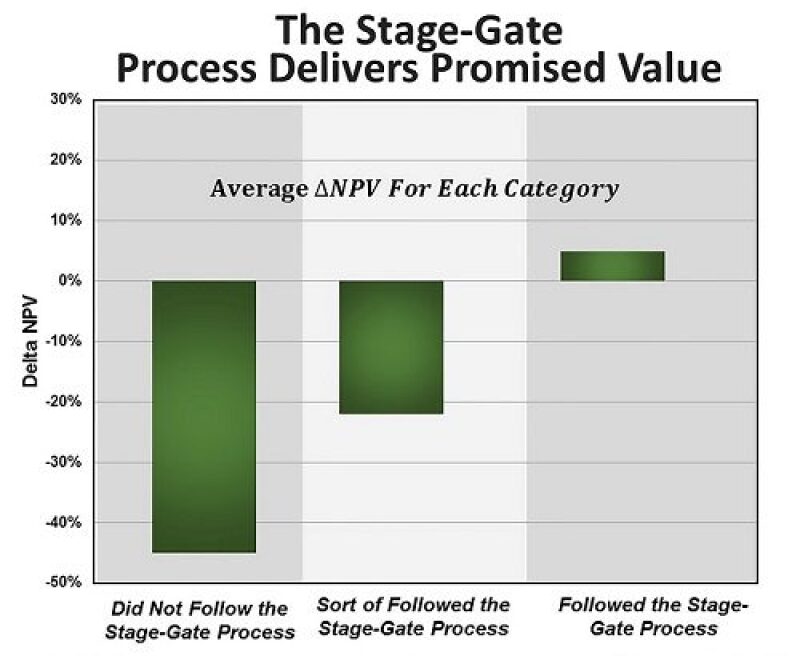

IPA’s project evaluations and research for its clients, grounded in data from more than 17,000 downstream projects, has proven that executive involvement in delivering capital projects is critical to preserving capital value. The average project loses 22% expected net present value (NPV) at authorization, according to IPA project data. Only 60% of projects meet all their business objectives once they are completed. Fortunately, executives can do a lot to increase capital project effectiveness and generate the shareholder-pleasing profits they aim to deliver.

A prime area executives should concentrate on to improve capital projects is the stage-gate process. Executives should embrace the stage-gate process. As the chart illustrates, IPA has definitive data showing that projects that follow the stage-gate process have much less deviation in delivering the opportunity value promised to shareholders. There is no getting around the fact that executives benefit from following a stage-gate process for delivering projects, but the process itself is not self-sustaining. It is up to executives to mandate that the project sponsor and team follow the process.

What some executives lack, however, is a sound understanding of the critical elements that make the stage-gate process work well.

Here’s a “Top 10 List” of what every executive should know about the stage-gate process:

10) The stage-gate process does not work without strong stage gates

Executives need to take stage-gate decisions seriously, only allowing a project to proceed to the next stage if the project data continue to support the viability of the business case.

9) Cost = Project Scope = Cost

Cost estimates given to business executives need to be expressed as cost estimate ranges. There has to be room for cost deviation to accommodate changes in the project scope.

8) Rules for setting cost contingency

Too little contingency means cost overruns. Too much contingency leads to waste, reducing capital effectiveness.

7) Use risk management effectively

Risk management is an excellent tool, but make sure known risks are fully recognized for what they are. Be willing to accept some risk and develop mitigation plans for other risks.

6) Insist on effective steering committees

Steering committees provide direction for the project, but be sure they don’t impede progress.

5) Take project definition seriously

As anyone who has worked with IPA knows, we take the relationship between project definition and project risk very seriously. Executives must understand that authorizing funds for a project with weak definition is a strategic decision—they are accepting a higher degree of risk compared to a project with quality definition. Projects with weak definition, on average, erode 25% of the value expected when funds are authorized for execution.

4) Establish requirements for building and supporting the owner project team

Owner-led project teams deliver better-performing and more cost-effective projects.

3) Take steps to develop clear business objectives

Undefined business objectives significantly increase the likelihood that a project’s cost will grow due to late changes in execution. Business objectives need to clearly state the business needs for a project so the project team can understand and act on them with certainty.

2) Recognize the benefits of framing a project before identifying the scope

The project frame forces executives to be disciplined about how an opportunity for capital investment is defined.

1) Identify the project sponsor

Regardless of the size of the project, executives need to decide who among themselves is accountable for the value of the project delivered; that accountability falls on the project sponsor. This role is critical to the project success. A couple of years ago, IPA began asking whether the company’s project system defined the role of the project sponsor. As it turns out, the project sponsor role was not defined or vaguely defined for 40% of project systems. When project teams are pressed, they usually tell IPA analysts that the project sponsor is the project manager or somebody else on the projects side of the project organization. But if you consider how most executives would feel about a project manager making business trade-off decisions, you get a clear understanding of why the project manager cannot fill the project sponsor role.

In conclusion, the executive role is vital in delivering capital projects. The project sponsor role is responsible for guiding the project team and ensuring adequate resources are available to optimize value in a capital investment. The stage-gate process instills accountability and must be followed to improve capital effectiveness.

The article was originally published on the Independent Project Analysis (IPA) website. Reproduced with permission.

Paul Barshop is a director of Independent Project Analysis (IPA) Capital Solutions, an IPA business providing hands-on client support. He was IPA’s COO from 2004 to 2015. Previously, he served as director of the Netherlands office from 2000 to 2004, serving European and Middle Eastern clients. Barshop is the author of Capital Projects: What Every Executive Needs to Know to Avoid Costly Mistakes and Make Major Investments Pay Off (Wiley, September 2016). The basis of the book started with a series of research studies done over an 8-year period, including Incomplete FEL 2, Destroyer of Value; Defending the Gate: An Examination of Gatekeeping in a Stage-Gate Process; Best Practices for Alternative Selection; The Dysfunctions of Project Governance Boards; The Role and Limitations of Project Assurance; and FEL 1–Setting the Foundation for Doing the Right Project. Barshop holds an MS in business administration from Boston University and a BS in chemical engineering from New Mexico State University.