The Oil Life Cycle

We’ll begin by playing a game, based on a riddle.

The following is a description of a word. Your task is to guess the word that matches the description:

It exists in so-called “reservoirs” that have developed over millions of years, and through a process of organic deposition, maturation, migration, and other means has changed into an abundant and dependable energy source on which modern economies are based. Companies explore for it using a mysterious technology called “seismic,” and follow up their exploration efforts by drilling wells thousands of feet into the ground and using exotic tools called logs to characterize the lithology, wellbore, and fluid.

Eventually, after drilling, running pipe, cementing, perforating, and more, the wells are finally ready to produce this magical resource.

After a well produces this resource, it must somehow be upgraded at production facilities, which can be a simple or intensive process, depending on the resource’s chemical composition, so it can be transported thousands of kilometers via pipeline (and rail in today’s market) to places called “refineries.” Only at refineries can it then be turned into marketable products by means of very intensive processes such as fractional distillation and catalytic cracking.

It likely took you only a second to guess the word being described is “oil.” The purpose of the exercise wasn’t to waste your time, but to provide an opportunity for appreciating the broad geological timeframe and general level of scale and complexity that precedes the consumption of oil-based products.

Given the oil industry’s vast scale and complexity, it is no wonder the public has formed many negative views. Statistics from a 2012 Gallup survey show that US citizens view the oil and gas business the most negatively of the 25 business sectors identified. In fact, the survey results show a similar trend of negativity for the oil and gas sector over the past 12 years.

What is really interesting about the Gallup survey is that the three most favorably viewed sectors are computer, restaurant, and retail, respectively. It makes sense that consumer sectors would rank highly: They generally market to and provide citizens with products that enrich their lives. But there is a disconnect stemming from the fact that a large portion of material and energy inputs that form electronic, food, beverage, and retail products come from byproducts of oil.

For example, according to a recent article by National Geographic, Americans purchase roughly 29 billion bottles of water a year. For manufacturers to make all these bottles, it takes close to 17 million bbl of oil, which is almost equivalent to a full day’s oil consumption in the US. More than 2.5 million tons of carbon dioxide are produced bottling that water, and the plastic produced has a higher calorific value than that of sub-bituminous coal.

Another example recently cited from a French online encyclopedia claims it takes 312 L (1.96 bbl) of oil to produce the materials needed for an average 24-kg computer and 612 L (3.84 bbl) to transport it to market.

The Oil Dilemma

Oil is undoubtedly a lynchpin of the world’s economy. Oil is the world’s most widely used source of energy, accounting for 40% of global energy consumption and an astonishing 96% of the energy used in the transportation sector. Yet even if we were to remove all gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles from the roads, we would still be dependent on this hydrocarbon.

One of the first applications of oil, dating back thousands of years, was as a medicine. Nowadays the most surprising uses include chewing gum, lipstick, and aspirin. Every barrel of crude oil holds remarkable potential: It helps keep us warm, helps keep us on the go, and provides the building blocks for countless products we take for granted. Plastics are a great example of this, with water bottles a notable illustration. Although there is a growing interest in the use of biomass as a feedstock, fossil fuels today form 99% of plastics’ raw material base.

So what would happen if humankind were to freeze oil production tomorrow? What would happen to plastics and other materials if oil production were to cease? At this time of high oil prices, due to scrutiny of reserves and exceptionally high growth in energy, these questions need to be asked more often.

Production of light plastic products, replacing traditional materials to reduce weight and fuel consumption, uses far less energy than traditional materials. Remarkably, even renewable energy sources are only viable with the use of plastics. Both solar panels and wind turbine rotors contain plastics. Another example would be the greenest means of transport, cycling. A total of 18 different plastics are used in the average bicycle. Some, offering durability superior to metal, are used in gears and pedals. Others make seats and handlebars more comfortable. The comfort and shatter-resistance of helmets is achieved with the use of liquid hydrocarbon foam polystyrene.

Where does all this plastic go when we’re done with it? According to the United Nations Environmental Program, global plastics consumption rose from 5.5 million tons in the 1950s to 110 million tons in 2009. A similar trend can also be noted for plastics disposal. In fact, Peter Jones, a British waste expert, predicted in 2008 that UK landfills might be mined for plastics and oceans scoured for the material within a decade due to high raw material prices. The Earth Institute at Columbia University claims that if all the plastic in US landfills were processed into liquid fuel, it could power all the cars in Los Angeles for a year.

Let’s be clear on something first and foremost: Oil will not run out completely for a very long time. As we have seen recently, when oil becomes increasingly scarce (both regionally and globally), prices rise to the point at which economies can no longer afford it for all applications. It becomes an economic hindrance for industries that utilize oil as a feedstock, increases prices at the pump, and eventually the everyday consumer starts to see prices rise for oil-derived products. In his book The World in 2030, futurologist Ray Hammond predicts that in the future oil will not be burnt away and wasted in energy and transport but reserved for “high-value processes and products such as plastics manufacturing … and energy trapped within the plastics can either be recycled or recovered and used for heat generation.”

Oil Awareness

So the question that arises is: Is the public aware of the end uses of oil? Whose responsibility is it to make the public aware of all the end uses of oil?

To help empirically explore these questions, we distributed a survey among respondents from Canada, the US, and various EU member states. To help support a true public view, 80% of the respondents selected had no oil industry work experience.

When asked what color comes to mind when they think of oil, almost all respondents indicated that oil is either black or brown, likely a depiction stemming from vivid images of oil spills such as those resulting from the Macondo blowout and Exxon Valdez disaster. Almost 90% of respondents guessed that the nearest oil facility was less than 300 km from their home and upwards of 70% of respondents felt that oil was not in short supply, as defined in the question as “less than 20 years’ supply.”

So in short, it would seem that the respondents are fairly well educated about oil, and indeed they are.

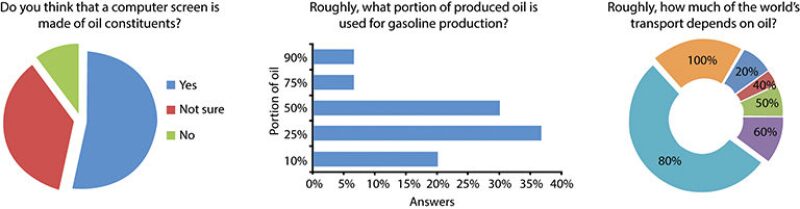

But some results indicated the existence of a disconnect. Respondents had difficulty categorizing how much oil is used to produce gasoline and how much oil is used to feed the transportation sector, as noted in Fig. 1. To be clear, the correct answers are 50% and 96%, respectively. Respondents were also quite uncertain regarding the extent to which oil is used in other consumer products, as exemplified in the computer screen question. (Interestingly, this happens to be the target of many advertisements showcased recently in Canada by major oil sands producers.)

The survey also asked respondents what their first thoughts are when they see an ad from an oil company. The majority of respondents answered by referring to the environment, saying either that oil companies should care more about the environment or that oil companies should help support the development of renewable energy sources. One respondent went as far as to say, “I think it is ridiculous propaganda full of half-truths,” which addresses the lack of trust the public might have toward both the industry and the ads. Another respondent mentioned that oil companies “should be putting more emphasis on the many uses of oil and how it really impacts people on a daily basis.”

What is clear from both the Gallup survey and our survey is that the public has had a negative view of the oil industry for quite a long time. Based on our survey results, respondents (i.e., the public) seem most displeased with an apparent lack of environmental consideration oil companies incorporate into their business practices. Yet an equally compelling argument could be that a lot of public negativity toward oil stems from a lack of understanding about our economy’s pervasive reliance on oil (i.e., the end uses of oil).

Other notable arguments might be that public negativity could stem from news stories by the media that tend to portray the industry negatively and could outweigh much of oil companies’ public relations and advertising efforts. Sometimes, however, advertising can work, even in the oil industry. An example of this is the presence of BP at the London 2012 Olympics, where they showcased their title sponsorship prominently across the Olympic facilities with their bright green and yellow logo.

So perhaps a fitting answer is that “the responsibility for education and for learning about the positives and negatives of our economies’ reliance on oil rests with both the industry and the public.” And if it seems warranted to make changes in how and how much we use oil, then all parties should understand what impacts could result from those changes. Then and only then can we say we are all making informed decisions about the future of oil.

| Jarrett Dragani earned a BS degree in mechanical engineering with a specialization in energy and the environment from the University of Calgary. He currently works for Cenovus Energy as a mechanical engineer supporting design and construction of the Christina Lake Oil Sands Expansion and has 3 years’ upstream experience working across various sectors of the industry in western Canada. He is a member of the SPE Calgary Section board as well as an editor for SPE’s The Way Ahead. |

| Maxim Kotenev is a reservoir geoscientist at Fugro Robertson in the UK. Previous responsibilities include geological and reservoir engineering work with Lukoil, Rosneft, and Technical University of Berlin, Germany. Kotenev was president of the Ufa SPE Student Chapter and currently serves as vice-chair of the SPE London Section YP Committee. He has coauthored 15 technical papers. Kotenev earned BS degrees in petroleum engineering and petroleum economics and management from Ufa State Petroleum Technological University, Russia; an MS degree in petroleum geoscience from the University of Manchester, UK; and a PhD in petroleum engineering from the Academy of Sciences, Moscow. |