Ocean waves are potential sources of energy that are powerful, often more readily available than wind and solar, and closer to population centers along coastlines.

But so far it is mostly just potential. Using the unpredictable changes of the ocean to drive the turbines of a large-scale floating generator is a problem, but hardly the only one that has yet to be solved.

“Wave energy current devices you put in the ocean need to be cost-effective and need to compete with what the other options are,” said Donald Gehring, president of Marine Energy Co.

The structural engineer, who has long made his living advising companies active in offshore oil and gas development, has developed a fascination with the challenges posed by wave power and has a design he thinks can reach the break-even level.

The construction price wave developers need to beat is USD 2 million per megawatt (MW) of capacity, according to the survey of the wave power industry Gehring spoke about at the Offshore Technology Conference (OTC 27667). That price target is higher than the cost for a utility solar plant but can compete because waves are steadier, generating power for more than twice as many hours per day than a solar installation, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

That differential means that a wave plant can make up the difference in the upfront cost by putting out more power per day over its life, if the machinery is up and running.

The design and the challenges it faces are an example of why there is reason to believe that wave power could someday compete with wind and solar, and also why it will be hard to get there.

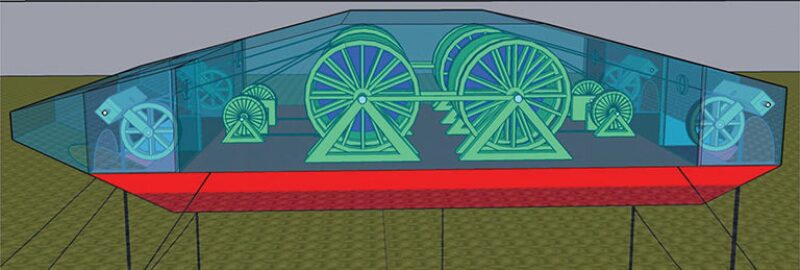

While he has seven patents to show for his engineering effort and a design for a large-scale electric generating barge he calls the Wave Catcher, Gehring says he should be spending more time promoting the project.

Most of the components are proven designs, from the standard barge used as a base to the large turbines adopted from the wind business. But he needs to raise the money to fill in the gaps that cannot be plugged with what is readily available.

If extreme weather hits, it will show how well the designer applied established principles on mooring lines, and also will test a device that is unique to a wave power barge—a system that rapidly loosens the tension on the vertical moorings that drive the power system before high seas cause serious damage.

Power is generated by the up and down motion of the vertical mooring lines. As the barge rises, the transmission system on the barge converts the energy from that motion to spin a flywheel at a relatively high rate of speed. An automatic transmission system is required to ensure the flywheel spins at the optimal rate, and a second such system is needed to lower that speed to the level that can be used by a turbine, which is the same design as the one used for offshore wind generation.

Creating an efficient system that quickly reacts to the changes of the sea, and one that can deal with its extremes, is one of the tough problems to solve, made harder by the need to limit the weight of the equipment on the deck of the barge.

Weight is another big issue. Heavier equipment reduces the efficiency of the barge by dampening the up and down motion that generates the power. The need to reduce the weight precludes some obvious alternatives, like using a bigger, slower-spinning flywheel because it weighs more than the faster-spinning one chosen. That quandary “has been a real tough nut to crack,” Gehring said.

Like others in wave power, raising money is a challenge. While investors are putting billions into wind turbines and solar arrays, they avoid risking money on technology development, and government money is increasingly hard to get.

Recently, the US Department of Energy rejected his application for USD 1.5 million to adapt an automatic transmission built to turn a variable speed input into a steady output—a continuously variable transmission (CVT)—for this demanding use, with the work done by the University of Texas-Austin and a CVT expert.

Gehring said his projections show a wave catcher can be built for considerably less than USD 2 million/MW, and his surveys have found other developers who say they can already meet the price target.

Wave power “will be your lowest-cost option in the near future,” he said, encouraging the hundreds of developers in this field to keep working to make “it cheaper and cheaper. Do not give up.”